Walls of Hope- Perquin and beyond:

The School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin/ Walls of Hope is an international art and human rights project of education, diplomacy building and community development born in Perquin, Morazán, in 2005.

Four Salvadoran artists/ teachers direct the school: America Argentina Vaquerano, Claudia Verenice Flores Escolero, Rosa del Carmen Argueta, and Rigoberto Rodriguez Martínez working in collaboration with Claudia Bernardi artist and educator from Argentina.

Walls of Hope is now expanding its art and community-based activities beyond El Salvador. One of the most relevant aspects of the School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin is the creation of art projects developing what is known as The Perquin Model, traveling from Perquin to Arambala, Segundo Montes and Cacaopera in Morazán, El Salvador; in Toronto, Canada; in Guatemala: Huhuetenango, Rabinal, Cobán, Guatemala City and the upcoming project in Cocorná, Medellín, Colombia.

The mandate of our school is to create bridges of collaboration through public art projects, site-specific interventions and weekly classes in painting, drawing, sculpture, educating children, youth and adults in the skills of the visual arts. Our vision is to add our efforts towards education, diplomacy, community development and the recovery of historic memory in our communities.

February 2008- Guatemala:

In February, 2008, The School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin was invited by ECAP ( Equipo Comunitario de Asistencia Psicosocial/ Psychosocial and Assistance Community Team) to work with survivors of massacres from Ixil, Ixcan, Chajul, Nebaj, Chimaltenango and Rabinal.

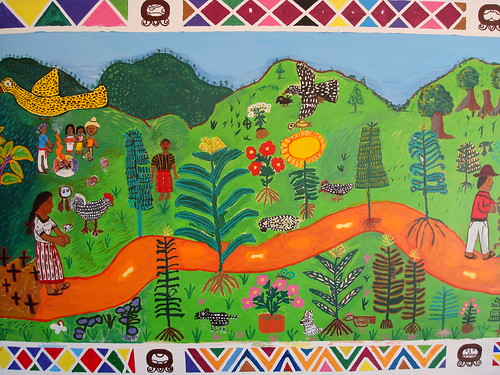

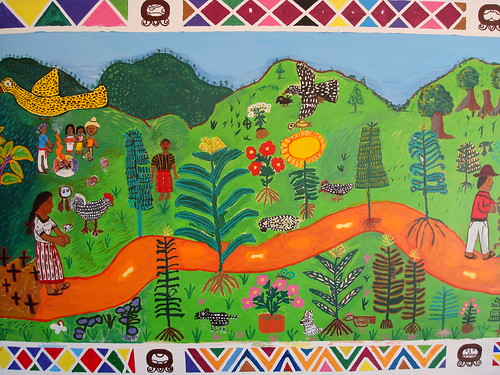

The large-scale mural (50 feet long X 5 feet high) was painted on canvas at ECAP headquarters in Guatemala City. The 35 participants of this project used art as a tool to collect and preserve their personal history as well as the historic memory of their communities that had suffered violations of human rights and state terror.

Our _compañeros y compañeras de ECAP_ saw in the work of art a monumental new way to relate to the victims. Psychosocial workers, therapists, human rights activists worked in collaboration with survivors of massacres in the creation of “Tapestry of History”.

Carmelita

Santos

Mural detail/ right section

Mural detail/ centre section

Mural Group/ Guatemala City, 2008

In May 2009, Adrianne Aron presented her book which is a translation of Mario Benedetti’s “Pedro and the Captain”. In her introduction Adrianne addresses the sad recurrence of torture as a system, infamously incorporated in the policies of the Bush Administration.

The cover of the book is a detail of the mural “Tapestry of History” that depicts the catacombs of official buildings turned into torture chambers.

Jeffrey Miller, from Cadmus Editions in San Francisco, generously has determined that the Publisher’s profits from this title will be donated to Walls of Hope.

Thank you!!!!! Jeffrey Miller and Cadmus Editions

August 2008/ Recovering Historic Memory with Indigenous Women Survivors of Sexual Violence in Guatemala

In August of 2008, ECAP invited the School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin to work with 30 indigenous women survivors of sexual violence during the armed conflict. This time, Claudia Verenice Flores Escolero, Rosa del Carmen Argueta and Rigoberto Rodriguez Martinez accompanied me to Huehuetenango in the north-western part of the country, frontier with Mexico overlooking the mountain range of the Cuchumatanes.

The participating women came from very far regions of Huehuetenango and beyond, bringing terrible stories of their pasts. They spoke Mam, Kaktchikel, Achy and Canjobal. They brought with them their interpreters who diligently translated each and all of the many important conversations that we had previous to the creation of the mural. Some of the women brought their children, who were respectful, adorable and totally immersed in the creative process.

After initial presentations and the sharing of ideas, the women dressed in their beautiful regional garments narrated some of the terrible episodes that have marked them and their communities during the armed conflict. I was unable to calculate the enormity of pain and the magnitude of the courage of these women who with no hesitation started drawing and rendering the start of the mural.

The women participants of this project were community leaders. Most of them had opened cases of investigation against the men who committed crimes against them. Some of those men are mayors of their communities. This evidence places the women and their families in great danger. No “elected” mayor would like to confront charges as a rapist.

The women were determined to speak their truth. They explained that they are not without fear but that it was important for their daughters to know what had happened to their mothers. They wanted to paint a mural. Murals are books with no words. They had seen other murals that collect the history of the communities under fire. They wanted to paint a mural that belonged only to their personal stories.

White papers on the tables, pencils, crayons, erasers and markers became lines, shapes, known and unknown people, animals, crops, sugar cane, corn plantations, houses on fire, army uniforms, children, some of whom were hurt, some were hanging from trees.

The women were silent while they drew. Some were crying and most were consoling one another.

Gesso was applied to the stretched canvas covering a surface of 18 feet long x 6 feet high. The edge of this mural depicted embroideries of the huipiles and cortes that the women wore, decorative colorful patterns based on concepts that expand from life and death, animals, plantations and water, people, community and children.

What is this mural about? I asked

What would you want to leave as a message?

Is there anything in particular that you want to say in this book of history of images and colors?

Unanimously, the women agreed to paint a heart in the middle of the mural perfectly centered and a house beneath it, three men in military fatigues, fat and menacing, memories landing gently on the surface of the canvas, terrible and brutal histories in the hands of these courageous women conjuring their worse days, their most frightening nightmares.

Camouflaged military airplanes, helicopters, people hanging from a tree with no fruits or flowers: The central part of the mural was becoming the “sad area” with a dark background and a spiral that absorbed life, an endless tunnel of sorrow. They painted weapons and destroyed houses.

The women decided to create a circle representing themselves holding hands, giving each other power, making a “belt” of strength in which the bad memories would not harm them any further. The sad memories would be contained within the restricted area. Outside the circle conformed by the connected women, they wanted to paint what they want for their children and their communities. The art process was allowing the women to see in other role than that of “victim”.

The mural expanded from the center and it acquired landscapes extending from the extreme left to the right, with corn plantations, pine trees, gardens and butterflies, a shinning sun located center right, children and a river.

We all participants of this mural project in Huehuetenango emerged from it transformed and marveled at how beauty and tragedy were merging in this mural.

In November 2008, the women who painted the mural presented it at the University of San Carlos. In front of an audience of 300 people they talked about their personal histories, they explained what the mural was depicting and why it was urgent for all Guatemalans not to forget what had taken place during the armed conflict that lasted over 40 years.

In an email dated March 3, 2009, Olga Alicia Paz, from ECAP told us that the mural was exhibited once more, this time at the National Palace, the Government House for the President to hear and learn what these women had gone through.

Olga Alicia writes:

Compañeros y Compañeros, esto es sorprendente!. Hay intersticios por donde metermos y lograr algun cambio, una denuncia y, quien sabe si mas adelante la justicia.

Compañeros and Compañeras, this is surprising! There are interstitial spaces where one can enter though and make a change, a denunciation, and who knows, may be in a near future we could arrive to Justice.

November 2008- March 2009- “The Environment Talks to Us”, Perquin, Arambala, Cacaopera, (Morazán)

The Environment Talks to Us is a collaborative art project for children and youth in the North of the department of Morazan, El Salvador, created from November 2008 through March 2009. The creation of these murals, painted on light and phone polls addressed in a visual form, the respect of the Rights of Children as proposed by the United Nations; the love and respect of the environment; solidarity amongst youth in the region; the respect of local indigenous traditions and the observation and dissemination of common history as a way to built communal development.

The Environment Talks to Us, an itinerant muralist initiative educated and trained children and youth from Perquin and beyond, ages 8 to 18 as, in the praxis and techniques of mural art.

The Environment Talks to Us proposed:

- Create public and collaborative projects of muralism.

- Create a public and collaborative demand of respect and preservation of the environment.

- Attract the participation of children and youth living in communities other than Perquin as protagonists of the mural projects

- Educate and facilitate children and youth in communities in the North of Morazan strengthening solidarity and community building alliances and the protection of the environment.

In vicinity of the presidential elections in El Salvador (March 15, 2009) the School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin was able to predict that the political propaganda would affect and intrude in the life of the communities. Dina, Claudia Verenice, Rosa del Carmen and Rigo (artists/ teachers of our school) and myself designed *The Environment Talks to Us* as a collaborative and community based project to be painted on public light and phone poles as well as on public vacant municipal walls to avoid the impact of political posters in the public sphere.

The target area was the public space that needed to be claimed by the community preserved and protected against political propaganda. The strategy of painting these murals by youth and children was a way to create a cultural patrimony that could not and would NOT be destroyed by political posters. The subject matter chosen by youth and children participating in this project was based on “The International Rights of Children” (UN). *This project was replicated with 150 youth in Cacaopera and with 50 children and youth in Arambala, both communities located in Morazán.*

Perquin, 2008

December 2008: Mural Project created by the Elderly from Perquin/ El Mural de los Abuelitos y Abuelitas de Perquin

In a recent email, America Argentina Vaquerano (Dina) and Claudia Verenice Flores Escolero told me that they had completed the second meeting with the abuelitos y abuelitos

Dina says:

It was very beautiful because there was an elderly lady who came with her ten year old granddaughter at 12 noon when the meeting was scheduled at 1:00 pm. She brought her sketches some of which had been made by her grandchildren. Some of the ladies brought tablecloths and embroideries because that is what they used to do many years ago, they were moved and eager like children and so were we, feeling a great responsibility to carry on this project well.

They say that the wall is too small for all that they want to paint. There were some sketches that were as if made by an architect! Some of they said that there were less houses and some of them said the opposite, that there were more houses than today. But we did reach an agreement: we will compile the sketches of the different drawings that they make and they will decide upon the selected sketches.

We want to collect the memories of the abuelitos / abuelitas in order to share that with the children, to see what the children interpret through the drawings. In this period of so much technology, it is a fact that we are losing the oral tradition between the elderly, the parents and the children, we would like that this project will serve to come back to sharing memories of the past to understand the present and to have the elderly tell their stories to the grandchildren.

Abuelitos y Abuelitas start drawing ideas for the mural

The mural that the abuelitos y abuelitas painted in collaboration with the School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin was inaugurated on December 18, 2008. It is located at the very entrance of the town of Perquin. It will be, indeed, a welcoming to everyone who arrives and visits the communities of the North of Morazan. Given their commitment, their enthusiasm and their observation that, perhaps, this wall is “too small”, we can imagine that this may be project #1 in a long series of projects addressing the memories of theAbuelitos y Abuelitas from Perquin.

The mural will serve as an art project and as a way to refocus on the many stories that the elderly of Perquin have which have not been told, or have not been yet shared with the youth and children.

Mural: Memorias de los Niños de Ayer/ Memories of the Children from Yesterday. Perquin, Morazan

Abuelitos y Abuelitas at the christening of the mural, December 18, 2008

THE PERQUIN MODEL

One of the most relevant aspects of the life of the School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin during 2008 has been the creation of projects all over the continent following what it has come to be known as *The Perquin Model.*

The Perquin Model could be defined as follows:

- A community based project that engages children, youth and the adults in the creation of art that serves as a component of community building.

- A project created with the understanding that there has been trauma, violence and prejudice inflicted to the participants given political duress, state terror, wars and armed conflicts

- The participants decide on the theme and narration of the piece with the intention to produce a visual testimony that represents their recent history.

- A collaborative art project that expands from creativity towards diplomacy, judicial concerns and the demand for the respect for social and human rights.

The community art projects created in the *Perquin Model* focus on the challenges posed by inter-communal and societal conflicts in today’s world. Our vision is to bring greater awareness through shared town meetings, through the planning of collaborative art interventions and public art pieces that recover historic memory encouraging professional skills in the arts and practical expertise and leadership to bear upon these challenges and to envision how better to prevent, manage and resolve such conflicts.

In April 2009, Carolyn Silberman and Kristin Kusanovich, Co- Directors and creators of JAI- Justice and the Arts Initiative at the University of Santa Clara, invited me as part of the guest artist series:

JAI: the justice and the arts initiative

Santa Clara University

guest artist series [ 08 – 09 ] presents:

The Perquin Model: Art & Diplomacy in the Process Towards Justice

Claudia Bernardi, Walls of Hope, Open Studio

CLAUDIA BERNARDI

INTERNATIONALLY ACCLAIMED ARTIST / ACTIVIST / EDUCATOR

TUESDAY, APRIL 14

MUSIC RECITAL HALL (MUSIC AND DANCE BUILDING)

4:45 – 6:15pm

About Claudia Bernardi

A native of Argentina, Claudia has traveled the globe joining AFAT, the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team, which has an international presence with a mission to “shed light on human rights violations and to contribute to the search for truth, justice, reparation and prevention of violations.”

Not only does Claudia assist in the excavation process, speaking out on human rights violations, but her art is informed by her own experience. She is committed to the use of art as an educational tool.

In El Salvador, she has founded the School of Art and Open Studio program of Perquin, located less than five miles from the site of El Mozote, where the massacre occurred in 1981. Now she is taking that model of collective recollection and art-making and finding transformative results working with refugees, survivors and at-risk youth in other countries such as Canada, the United States and Guatemala.

An internationally renowned artist who works in the fields of human rights and social justice, Ms. Bernardi has exhibited her work in over 40 solo exhibitions. In all of her work over the past two decades – whether as an artist through installation, sculpture, and printmaking, as an educator through teaching and lecturing, or as a participant in human rights investigations – she has impacted thousands of people with her integrity, compassion, and truthfulness. She is an artist who has witnessed monstrous atrocities and unspeakable human tragedies, yet speaks of these horrors in ways that communicate the persistence of hope, undeniable integrity, and necessary remembrance.

Community members who are interested in El Salvador and Latin America in general will find her approach to be critical for our times. Those who have partaken in immersion trips or who hope to someday travel to El Salvador will not want to miss this dynamic and inspiring event.

Please join us for this remarkable lecture by one of the world’s most profound thinkers on the arts and human rights.

Carolyn Silberman and Kristin Kusanovich

Co-Directors of the Justice and the Arts Initiative,

College of Arts and Sciences, Santa Clara University

The Perquin Model traveled in 2008 to:

WALLS OF HOPE-CANADA- APRIL – MAY 2008

PROJECT HISTORY

Julie Jarvis and Claudia Bernardi met in 2006 in Northern Ireland in the context of “YouCAN” conference which addressed Youth, Art and Education in zones of conflict. Since then, Julie and Claudia have been thinking about a way in which to connect common visions and strategies in an art project reaching youth locally and across borders.

The project was originally conceptualized as a multi faceted, multi layered gathering of youth that, like in El Salvador, would not only produce art but create art as a way to understand and investigate history and learn about human rights and social justice. Our initial challenge was to find the artists in the same country, since Claudia spends half of the year in El Salvador where she created the School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin, Morazán.

The next step was finding a team of Toronto youth to take ownership of the project. Once the youth planning group was formed, they were able to articulate and develop the project in a way that was meaningful and relevant to them. At the outset they decided to target a diverse group of youth from the different boroughs of Toronto, who represented different ages, abilities, cultures and experiences. It was particularly important to them to gather a group that reflected the diversity of our city/world and include newcomers, First Nations and disengaged youth. In recruiting this group of youth, we are grateful to our many community partners who worked with us to find young people and even accompany them so that they could participate.

Recruitment was based mostly on the youth’s willingness to be part of a collaborative artistic process; the majority of the members of this group had never worked with art before.

First meeting with youth

Once the project began, we were touched by the respect, interest and commitment the group expressed to the art and each other. As we worked together – learning about historical tragedies and human’s rights injustices and artists who use art to resist and fight for social change, we quickly began to see the commonality of the human experience (joys and sorrows) throughout the world and throughout history. “Why?” asks Lyla “does human tragedy and violence repeat itself over and over? “Why do we not learn from our mistakes?” And then after reflection the group as whole wondered, “Is ‘Why’ really the question”?

As the youth began to realize their ideas and collaboratively explore their own response to these issues, the installation grew beyond anyone’s expectations. Our originally 5-week project timeline was extended to 10 weeks to complete all the different pieces. Over the course of this process, the youth have completely taken ownership of the project, creating, debating and deciding on its content and presentation.

Leyla and Claudia

Irma

Community outreach and partnership for this project has been extensive and ongoing. Since the project started we have had many visitors to our site and received invitations from different groups to give talks and show our artwork. On June 14th, documentation of the Walls of Sorrow/Walls of Hope project went on display at the *(Bridging) Walls of Hope Exhibit at the San Francisco Children’s Museum* where it was shown for the month of June, 2008.

Cat and Heather

Paintings based on silhouettes

Due to the success of the project and enthusiasm of the participants, Julie Jarvis and Claudia Bernardi have committed to continue working in partnership with the young artists to expand and develop this work and create more Walls of Hope – Canada – 2009.

WALLS OF SORROW/WALLS OF HOPE

A journey from Darkness to Light

Since April 20th, 30 Youth from diverse backgrounds across the GTA have been working together on weekends with international artist Claudia Bernardi (Artistic Director of the School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin, El Salvador), and a team of local artists led by Julie Jarvis (WSWH Producer/Project Coordinator) to build a collaborative art installation that explores global poverty, human rights, and building community through art. This multimedia installation, which combines video, documentation, sculpture, painting, dance, theatre and sound sculpture is being built by the youth at AGO Gallery School and Sketch and will be exhibited at Metro Hall and City Hall this summer.

Cinthia and Karla

Kayene and Julie

Rachel (age 14) says she hopes that when people walk into the installation space they will feel ‘power’ – a sense that ‘ I can do something’. ‘I can change the world’.

The project was planned and developed by a team of six youth who represent different ages (14 to 24), backgrounds and communities. These youth, who are called the ‘Weavers’ (because they weave the different elements of the project together) come from across the GTA – Toronto, Scarborough, East York, Etobicoke and Richmond Hill and are volunteers from youth and arts organizations – AGO Youth Advisory Committee, the AGO Gallery School, Delisle Youth Services and Phoenix Community Works Foundation. They have been meeting regularly at the AGO since January with Julie Jarvis to plan and design the project. The planning team also received ongoing feedback and support from the AGO Youth Advisory Council, led by Syrus Ware.

Luis

Berry

As creators and visionaries of the “Walls of Hope’ project, the youth have become creators of a unique partnership that crosses sectors, communities and countries. Together they are using art as a way to build bridges of diplomacy and understanding locally and with areas of the world deeply affected by war and the painful transition in the aftermath of war.

The *Walls of Sorrow/Walls of Hope installation* was exhibited at the Metro Hall Rotunda (55 John Street) from July 14th to July 19th. Opening reception will be held on July 14th from 6:00pm to 8:00pm. A travelling exhibit (including our paintings, documentation and Wall of Hope Sculpture) was exhibited at City Hall Rotunda from August 13 to the 17th 2008.

Leyla and Alana

THE INSTALLATION

The installation is a journey – from darkness to light, from ignorance to awareness, from despair to hope, from prejudice to empathy. It explores the ‘power of art’ and how art can be used as a tool for transformation and a proposal for diplomacy and conflict resolution.

The installation includes 7 major pieces:

- The Walls of Sorrow – Two tunnels containing video projections of dance, theatre and sound sculpture.

“Hear no Evil/See no Evil/Speak no Evil” is one of the pieces included in this piece. It is about the genocide that happened in Residential Schools. “Hear no Evil/See no Evil/Speak no Evil” shows how the Aboriginal culture and language was taken from the students that attended these schools and how it tore them apart emotionally. - ‘La Gritona’ Paintings – a series of 13 portraits (2′ x 5′)

These vibrant and powerful paintings express the youth’s sorrows and hopes for the world. - The “Points of View” Sculpture

This mixed media sculpture, explores different points of view about the same issue (both are true). The sculpture highlights key issues of concern to the group – poverty, war, violence and discrimination. These are explored from both a local and international perspective.

- “The Shoes of Another” series of 9 sculptures

Nine foot casts placed at different points along the journey ask the question: “What does it mean to stand in someone else’s shoes?”

- “The Well” (of Hope)

A point of departure from the tunnels of darkness, “The Well” is located in the centre of the installation and is a still point where the viewer is invited to reflect and go inward. Symbolizing the transformative journey one takes to find light in the darkness and within oneself in order to have strength to help bring peace to the world. - The Wall of Hope – sculpture, sound and video:

The Wall of Hope is a 6′ by 7′ two-sided sculpture. On one side, there is a wall where visitors can write and place their hopes for the world. On the back is a video projection – interviews with the youth involved in the project. Suggesting that the real hope in the world is the youth who have the courage to come together to explore social issues and express their voice so poetically to the world.

- The Book

Placed on a tall stand built to the dimensions of the book itself, it includes a compilation of images and words by participants.

The Walls of Sorrow/Walls of Hope is a project created from the Phoenix Community Works Foundation, in collaboration with the Art Gallery of Ontario, Sketch and community partners.

Walls of Hope-Canada is funded by the Laidlaw Foundation, community sponsors, partners and private donors. We are grateful to our supporters at the AGO – Syrus Ware, Program Coordinator Teens Behind the Scenes; the Gallery School, Jane Lott, Howard Esben (former Program Manager) and Sheila Dietrich (Chief Technician), Margo (Studio technician) and Sketch – Rudy Ruttiman (Executive Director), Phyllis Novak (Founder & Artistic Director), Heather Bain (Apprenticeship Program Coordinator) and Michael O’Connell (Musician & Sound Technician). We are also deeply grateful to our artist facilitators & artistic advisors who donated their time and energy to support the youth and help realize the project: Koruna Biswas Schmidtmumm (visual artist and ‘foodie’, Erick Portillo (photographer & ‘foodie’), Lindsay Smail (photographer and designer) and Sheila Dietrich (Installation Artist & Advisor). We also had artistic & technical advisors: Sheila Dietrich and Jan MacKie. These individuals and organizations made this project possible by laying the foundation for our Walls of Hope.

Julie Jarvis and Claudia Bernardi

ART OF ONE WORLD, ART AND GENOCIDE CONFERENCE AT CAL ARTS, CALIFORNIA

Erik Ehn, playwright and dean of theater at Cal Arts, continues to convoke artists working with issues regarding political violence, state terror and genocide, in the conference he envisioned few years ago called: *ART OF ONE WORLD.*

The agenda of the 2009, conference held at Cal Arts in January 2009 was:

_Motherhood and Revolution: How women, and mothers in particular, are innovating in conflict and post conflict circumstances, and expanding the model for ways in which one is an artist/activist in the world._

_Each day will begin with a presentation that lays out some of the social and historical background of various topics, in an effort to make clear that legitimate moral stands and elections need to take place (simply: this happened and must be witnessed to), and also that simplicity is beset with numerous challenges on the one hand – we must avoid over simplification, or – for example – an orthodoxy of permanent victimhood; on the other hand we must avoid overcomplicating the record to the point where moral position is mooted._

In the context of this conference focused on the role of women and mothers, I presented the work created in August 2008 by Indigenous Women survivors of sexual violence in Huehuetenango, Guatemala.

The presentation was very well received leading to conversations, debates and sharing of urgent issues proposing a demand for peace and legislation that would endorse the peace process in the Middle East, Central America, the Balkans, Africa, Asia and indigenous peoples of the world.

…………………………………………………………………….

FEBRERO, 2009- COBAN- GUATEMALA

“SHAPING OUR HISTORY”, Sculpture Project in Purulá, Baja Verapaz with 35 Q´eqchies women, Survivors of Sexual Violence during the armed conflict

ECAP invited Claudia Verenice Flores Escolero, Rosa del Carmen Argueta, Rigoberto Rodriguez Martinez (artists/teachers from the School of Art in Perquin) and I to work in an art project with 35 Q’eqchies women survivors of sexual violence during the armed conflict. This project “Shaping Our History” took place in early February of 2009 in Cobán, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala.

The participating women, ages 20 to 65, said that working in art was a way to remember together, of “building” together. The women remembered the tragedy of the war and violence in solitude: “it pains the heart and dulls the mind”. They expressed the feeling of being protected by the presence of the other women. Together, they felt their strength. The body is a book of history: the hands remember, the feet remember, the skin remembers. The collective and community artwork would be telling those stories demanding justice and imagining a world less painful for the future of their children.

The participating women said that for them, to create this art project together was a way to investigate the magnitude of the damage, but also to witness that they are dignified women, still standing on their feet demanding to get back that which they had lost.

Olga Alicia Paz, Ana Alicia, Aydeé, Cruz y Angelina, members of ECAP were support team and translators.

What story would they want to tell?

This was a paper sculpture workshop taking place in Cobán, the first of this kind initiated in Guatemala. This accessible and “cheap” technique was developed by the wonderful teachers of the School of Art in Perquin in an effort to use available and not expensive materials such as newspaper, masking tape, white glue, gesso and acrylic paint . The sculptures are formed by modeling the newspaper with masking tape, which wraps the paper and gives shapes to figures emerging from it. White glue is applied as a way to protect the piece. Gesso gives strength to the sculpture and prepares it for the last step: the painting of the piece. A final varnish is applied for protection and longevity.

The sculptures created by the women in Cobán are theatre pieces, acquiring a sense of denunciation and drama, depicting army men, menacing soldiers, animals and houses. Most importantly, depicting themselves as threatened women, women in pain or danger, women protecting their small children or, tragically, failing to do so.

They shaped their personal histories modeling newspaper in their trained hands.

Over the years, they had felt punished not only for the atrocities that they had gone through but by the imposed silence that shrouded their existence. The sculptures were the first attempt to converse openly, communally and safely, about what they had seen, experienced and survived.

In the evaluation period, I asked them what they thought about the process and about what was emerging from it.

They all agreed that they felt insecure at first, mostly, because they are illiterate and they feel that they cannot write their personal history. However, the making of the sculptures that was, indeed, a way to narrate what happened made them happy and willing to continue sharing that which is their most personal secrets of shame and pain.

Olga Alicia Paz proposed that the finished pieces would be exhibited on February 28 at the Government House together with the mural painted in Huehuetenango in August 2008. This was going to take place within the context of the 10 years anniversary of the creation of the Commission for Historic Elucidation. The sculptures were going to be shown also at the National Theatre. Olga Alicia also proposed to create a book containing the message that the women would want to deliver and the photographs of the women creating the sculptures to be taken to Sepur and Jolomijix.

What does your image represent?

Each sculpture is a testimony, and indictment, an irrefutable evidence.

Maria Pop, from Tres Arroyos, made a complex structure: a tree and a man hanging form a tall brunch.

She added:

_“That is what the army used to do. I witnessed how the army would take the men, our husbands, brothers, sons, fathers, and they were tortured before they were hanging. I made myself pregnant, as in fact I was, at the time the army came to our community. I made a pot next to me on the ground. That represents that we, the women, had to escape to the mountains, with the little we had. We were refugees in the forest until the army would catch up with us. There was no way out.”_

The sculptures narrate unknown realities; they are segments of information that are presented to us humbly and pursuantly.

The last day when we had all the sculptures finished and all the women were photographed with their “dolls” as they ended up calling them, one of them came to me and said:

_“These “dolls” help us take the darkness out of our hearts.”_

…………………………………………………………………….

February 2009/ THE JOURNEY TOWARDS JUSTICE

Mural painted by survivors of torture and massacres

in Rabinal, Plan de Sánchez, Río Negro, Ixil, Ixcan, Nebaj and Chimaltenango.

From Cobán, Claudia Verenice Flores Escolero, Rosa del Carmen Argueta, Rigoberto Rodriguez Martinez (artists/teachers from the School of Art in Perquin) and I went to Rabinal, Baja Verapaz to work on a mural project with 35 men and women.

This project was part of an effort called: *Torture/ Prevention and Rehabilitation in the Multicultural Context of Guatemala* gathering survivors of torture who are also survivors of the massacres of Rabinal, Plan de Sanchez, Rio Negro, Ixil, Ixcan, Nebaj and Chimaltenango.

To work in a project of this scale is challenging but, what it was remarkable in this case in that there were seven languages spoken at all times. To find a thread of common accordance was a long process due to the need of translators.

The subject of the mural was not yet decided when we started painting the first layers of colors. It seemed to me that most of the participants were clear in making a visual rendering of their personal histories. Some of the participants had seen the mural created in Huehuetenango the year before and strongly gravitated to the idea of narrating while painting.

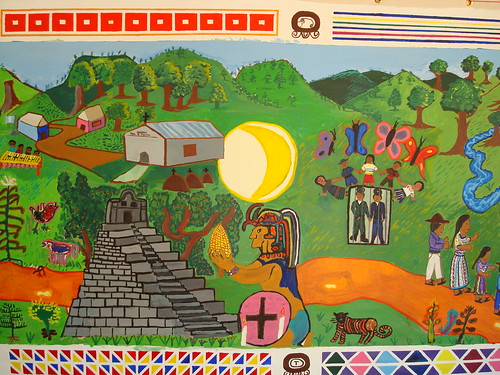

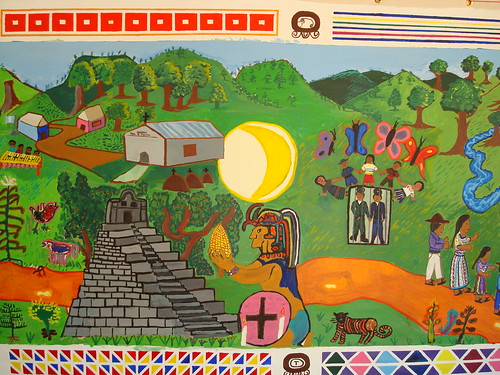

The mural was huge! 45 feet long X 6 feet high. The canvas was stretched on the back wall of the hotel where we were all staying. The environment where we painted was sunny and airy.

Lidia, Olinda, Andrea, Santos, Sarita and Pedro, Promotores de Salud Mental from ECAP had worked with us in previous mural projects. Their participation and help made the process agile and better organized. Two new compañeros from ECAP joined us: Yadira and Eduardo.

After deliberation and compromises, the participants came to the agreements that the mural should address the long journey towards justice. They all had survived the tragedy of war and violations of human rights, but this mural so dear to them would focus, they hoped, not in the rendering of the destruction of their communities, the loss of family members and the personal suffering, but in the tenacious and persistent demand of justice. Once the theme was selected, the images appeared with no hesitation as if all the participants were in total accordance of what to say, and why to say it.

The composition was established upon a path, a walk -way, a transit.

The borders of the mural , as it was the case in previous murals, was decorated with designs that identify the communities and regions from where the participant are from. The left side of the mural shows a community in flames, military helicopters are dropping bombs and civilians are escaping to the mountains. Some succeed, many do not.

There is a young woman dressed in garments from Chimaltenango in the foreground. We are seeing her showing her back to us. She does not look at the viewer. She looks at the scene of destruction. She has a large sun above her head, as a way to represent that she is a young woman of the present being protected by her ancestors in searching for the painful truth of the past.

To her right, the path-way starts as a long and winding walk way, transited by many people. Those are the ones who survived state terror and are willing and able to give testimony. There is a gathering of people around a table representing the first organized groups of victims that were the founding stone on which the human rights organizations have been built.

The center of the mural shows a dead tree, dry and lifeless purple. It seems to be planted on a clandestine cemetery where the crosses bear no names. Those are the hundreds, the thousands of people disappeared in 40 years of war.

From the high brunches of the tree, new life is growing, tender leaves of fresh green are showing that life is possible again and that it can only exist if everyone is part of a communal intention to recommence.

Two birds looking at each other in agreement crown this tree of death and life.

The orange path of committed transit towards justice expands towards the right of the mural demarking agriculture, forest, animals and arriving to a Mayan pyramid where a Mayan Priest is presenting the sacred offering of Corn to the Gods. His power is unquestionable. The Mayan Priest has the sun and the moon upon him. The universe assists him. Sadly, above the sacred ritual of corn, there is a building. That is the church of the community of Plan de Sanchez, Baja Verapaz where on 18 July 1982, over 250 people (mostly women and children, and almost exclusively ethnic Achi Maya) were abused and murdered by members of the armed forces and their paramilitary allies.

The massacres of Plan de Sánchez, Rabinal and Rio Negro were parts of the government’s scorched earth strategy. The survivors were told that reprisals would follow if they spoke about the incident or revealed the location of the numerous mass graves they had helped to dig.

Poignantly, the mural journeys to its right side, by showing a group of organized civilians with a sign that says: “NO A LA REPRESA”/ WE DO NOT WANT THE DAM” and a lot of people, mouth open, screaming their right to object the building of a new dam.

In 1978, in the face of civil war, the Guatemalan government proceeded with its economic development program, including the construction of the Chixoy hydroelectric dam. Financed in large part by the World Bank and Inter-American Development Bank, the Chixoy Dam was built in Rabinal, a region of the department of Baja Verapaz historically populated by the Maya Achi. To complete construction, the government completed voluntary and forcible relocations of dam-affected communities from the fertile agricultural valleys to the much harsher surrounding highlands. When hundreds of residents refused to relocate, or returned after finding the conditions of resettlement villages were not what the government had promised, these men, women, and children were kidnapped, raped, and massacred by paramilitary and military officials. More than 440 Maya Achi were killed in the village of Río Negro alone, and the string of extra-judicial killings that claimed up to 5,000 lives between 1980 and 1982 became known as the Río Negro Massacres. The government officially declared the acts to be counterinsurgency activities – although local church workers, journalists and the survivors of Rio Negro deny that the town ever saw any organized guerrilla activity.

*The long path towards justice / El camino hacia la justicia* will continue to expand through the lives of many peoples and generations to come in Guatemala until the truth be known, until punishment to the responsible ones will be given, until the peace process will be granted to everyone.

The mural is currently traveling to the communities where the participants of this project are from.

The IACHR began processing a complaint and received a partial recognition of the state’s institutional responsibility from democratically elected president Alfonso Portillo in the first year of his term, and finally referred the case to the Inter-American Court of Human Rights for judgment and settlement. In 2004, the Inter-American Court issued two judgments, in which it established Guatemala’s liability in the case and ordered an extensive package of monetary, non-monetary and symbolic forms of compensation for the survivors and the next-of-kin of the deceased.

Claudia, Claudia Verenice, Rigo, Rabinal, 2009

…………………………………………………………………….

MORE ABOUT THE PERQUIN MODEL

In addition to the work created in Perquin, El Salvador, in Toronto, Canada, and in Guatemala, the *Perquin Model* has become part of the subjects that I have included in my classes at the *California College of the Arts* where I am Professor of Community Arts Major.

Students at CCA continue to investigate the success and challenges of the work created in El Salvador, Guatemala and Canada. They study the methodology implemented in these projects and investigate how the “blue print” of the interaction between art and social justice can be further transported to the United States where their are finding their voices and their role as artists in communities.

I have lectured extensively at universities and colleges where the interest in accepting art praxis as a component of community building and the reinforcement of social justice has become a point of departure for the creation of new courses, curricula development and professional new forms of defining what it means to be an artist in the first decade of the XXI century.

February of 2009- MARY BALDWIN COLLEGE arrives to

Perquin

* One-Week Trip to El Salvador: “Witnessing the Peace Process” February 28- March 8, 2009.

# MBC Students were in Perquin, Morazán, for 6 days, working as Artists in Residence at the School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin, a community based, collaborative art initiative/ project that serves children, youth, adults and the elderly. Students worked in art in community projects investigating strategies that the school uses to build bridges of diplomacy through art practice.

# MBC students were immersed in the recent history of El Salvador and the legacy of the Civil War, 1980-1992. MBC students met the community and community’s leaders who had been active members of grassroots organizations in the postwar time. Through lectures, visits and conversations with ex combatants, survivors of massacres, political leaders and Salvadoran artists, MBC students were introduced, educated and guided on how to implement community based projects such as murals, public art, film and video documentation and visual art. Professor Bernardi oversaw, directed, helped execute and gave guidance to students on how to successfully design and carry on art in community project.

# During a trip to El Salvador, MBC students spent two and a half days in San Salvador where they met lawyers and human rights practitioners who had been designers and participants of the Peace Process proposal, the Truth Commission and local human rights agencies. Students had the opportunity to meet, converse and learn about the successes and failures of the Peace Process and the arduous post war period.

# MBC Students visited the Museum of Words and Images, in San Salvador, directed by Carlos Henriquez Consalvi, Santiago, seeing photography, documentaries and testimonies of the 12 year civil war in El Salvador.

_STUDENTS WITNESS PEACE IN PROGRESS IN EL SALVADOR_

*MBC Magazine*

*3/4/2009*

“An artist is, above all, an optimist.” Not a typical beginning for a course syllabus, and the class it goes on to describe is not typical, either. For starters, it takes place in El Salvador and is led by dynamic MBC Artist-in- Residence Claudia Bernardi. As one of Mary Baldwin College’s Spring Break offerings – ocurring March 2 through 6 – the course Witnessing the Peace Process promises to be a journey measured in more than just miles.

“Analogies can be drawn between the creative process, the building of community, and the proposal and implementation of a peace process,” wrote Bernardi, who is one of MBC’s artists in residence.

Their timeframe in El Salvador is short — just about seven days — but readings and weekly meetings guided by Bernardi’s syllabus prepared students and accompanying faculty members since the beginning of the semester. The group is slated to spend two days in San Salvador, where it will meet lawyers and human rights practitioners involved in the peace process in that country, and visit the Museum of Words and Images to view documentaries, photographs, and testimonies of the country’s 12-year civil war.

The remainder of the trip will be spent in Perquin, where Bernardi established Walls of Hope Open School and Studio to help heal the wounds of one of the civil war’s brutal massacres at El Mozote.

—End of Transcript

What follows in the description of the experience in the words and reflection of one of the students part of the Perquin trip.

_EL SALVADOR: REFLECTION, DUTY AND LA VERDAD_

*Hannah Scott*

*April 5, 2009*

*Mary Baldwin College*

_Ellos no han muerto

Estan con nosotros,

Con ustedes y con

La humanidad entera_

“They did not die. They are with us and with you and with all of humanity”

I began to board the plane, a small Salvadoran child skipping past me, exclaiming “Avion” He was, on the outside, just as I felt on the inside; a frenetic bundle of nervous excitement in my chest like I had never experienced before. My first flight, my first experience outside of the United States, my first chance to stand shoulder to shoulder, face to face with people that had experienced loss and hope in a way that I still had trouble fathoming. And then I was there, in the valleys of Morazon, where everything was simultaneously brand new and yet strangely familiar. I had read so many books on the region, the country, the people, the politics, the twelve-year civil war and now every detail was breathing all around me, like a steady presence; a reminder. So often United States citizens come and go in various countries all over the globe with no understanding of the people or the history, all that comes to mind for them is the exchange rate. However, El Salvador is a country which demands preparation.

I remember thinking, and later journaling, that on the surface everything about this place is perfect, aside from the gaping, still healing wound that is the face of El Salvador. These people have seen and felt and come back from such horrendous human setbacks and yet they are kind, hospitable, generous and, most surprisingly, hopeful people. They haven’t given up, like so many have in the countries that surround these boarders. Jorje, our guide, had made that clear. These people move forward every day, and it is evident. However, I am certain that every person that has visited this country in the past thirty years has been changed for it, in numerous ways. Joan Didion, in her book Salvador, writes poignantly of the country and it was only after returning to the U.S. and rereading this book that had helped prepare me for the trip that I really started to understand the sentiment.

She writes “whenever I hear someone speak now of one another solution for El Salvador I think of particular Americans who have spent time there, each in his or her own way inexorably altered by the fact of having been in a certain place at a certain time. Some of these Americans have since moved on and others remain in Salvador, but, like survivors of a common natural disaster, they are equally marked by the place”.

I found this entirely true. I feel linked to the country, and to the people, and to my companions that I traveled with. It is a feeling one reads about in novels, sees painted on the faces of great actors in great epics. It is not a feeling I thought I’d experience this early in life. I can liken this feeling to that of seeing a ghost, and though every moment in Salvador was relished, there are ghosts all over the country, traces of the past that if taken the time to look for, are absolutely everywhere.

One of the things that I considered every day of my journey abroad that troubled me was our part in this conflict that waged far longer and reached much further than the twelve years described in our texts. The United States played a significant role in the Salvadoran Civil War and though no one talks about it eagerly, I feel that it is most likely widely known by those who have lived through the war. Yet, as mentioned earlier, they are a kind and hospitable people towards those hailing from the States. The United States government chose to ignore much of the situation while also choosing to fund a great deal of it, supporting massive human rights infractions by giving enormous amounts of military aide. When news of the massacre emerged a few weeks after the incident occurred, the Reagan administration chose to call it propaganda. Mark Danner writes of the Massacre at El Mozote with startling, provocative detail and every last, sordid fact, one of which is that “by early 1992, when a peace agreement between the government and the guerrillas was finally signed, Americans had spend more than four billion dollars funding a civil war that had lasted twelve years and left seventy-five thousand Salvadorans dead.”

By then, of course, the bitter fight over El Mozote had largely been forgotten; Washington had turned its gaze to other places and other things. For most Americans, El Salvador had long since slipped back into obscurity. But El Mozote may well have been the largest massacre in modern Latin-American history.”

How can a people not be angered or affected outwardly by these facts? Has it simply been long enough for them to put down that burden? Because of these assumptions, I thought that we would be ill received upon arriving in El Mozote due to our gringo skin and broken Spanish but the kindest people I met during the entirety of the trip lived in the hamlet of El Mozote, or in the quiet neighboring town of Perquin. Those that I speak of welcomed us heartily and smiled genuinely. Though I tend to journal more about my reflections, reactions and gut feelings and less about itinerary, our time at El Mozote proved differently. I wrote of the place that night with profound feeling, writing that “we arrived in El Mozote this morning and while every gut instinct and fact I had acquainted myself with about the place flooded to the surface, my surroundings were strangely surreal and oddly calm. Still. Like an empty, blank sheet of paper. Scorch the earth. Leave nothing living. La Limpieza. La matanza. It’s as if the town itself was wiped away, effectively erased. A new town emerges. Smaller. Humble.

Only a few families; only a few children play in these streets where nearly one hundred and forty under the age of twelve were machine gunned and forgotten in a space smaller than a dorm room. While there we listened. We walked where they had walked. We saw where they had hid, where they were killed, like dogs, their final moments punctuated with the kind of inhumanity that I’ve only seen in macabre movies. I hiked up the hill to the top of the mountain where the prettiest and youngest and frailest had been raped and tortured and shot and then burned. I was burnt by the sun while on the hill, as if a kind of revenge. There are still bullet holes, like open mouths begging to be heard, M-16 shells which exploded into shards upon impact. I played soccer with three young boys, happy for my company despite my pale skin, no translation required. I felt my youth spring to life, seep into me. I met a woman with the most beautiful face I had ever seen; she must have been in her eighties. I clumsily asked in broken Spanish if I could take her picture. Puedo tocar una photographia de usted? She beamed a toothless smile, her face illuminated, accepting me. And then it was over too soon”. Thinking of it today is just as vivid as if I were right now standing beside the small crab-apple tree where Rufina Amaya had hidden from the Atlacatl Battalion. The very battalion that had been trained with tactics developed by and taught through the United States Special Forces personnel along with the leadership of Lt. Colonel Domingo Monterrosa. However the combination of leadership and U.S. training bread something different in this case; something else was instilled in the battalion – a certain type of aggression that the Salvadoran citizens had not anticipated that day. “They seemed a somewhat different breed from most Salvadoran soldiers – more businesslike, grimmer even – and their equipment was better: they had the latest American M-16s…” The end must have been so horrific, and I found myself wondering if these children with whom I played soccer with had even the faintest idea about what had occurred upon this soil which caked their bare feet.

When we began the mural at the Sixth of January Community Biblioteca, I had dozens of thoughts about the country marinating in my head. I had to push some aside so as to work diligently with this community. Everyday of the painting process children would file into the streets as the afternoon wore on to help paint and contribute in the ways that only a child can. It was beautiful. And I began to see how hope for the next generation could be the answer to all of my questions about why these people don’t hoard some kind of awful but rightful hatred for us. The mural turned out magnificently and I know that all of us became closer because of it. Leaving that community was terribly difficult and I did, in fact, become a bit choked up and failed to hide my feelings.

Before leaving Perquin for San Salvador, the country’s capitol city, we returned to El Mozote. It was the two-year anniversary of Rufina Amaya’s death, and we wanted to pay our respects. It was bittersweet, quite sad, and profoundly important to me. We bought two rose bushes by the side of the road and planted them by Rufina’s grave. I don’t cry often. And I didn’t cry then. But it makes me want to cry now. I dug a hole. I put my hands in the dirt where she laid. I promised her, and myself, and all of humanity that I would continue her story that she fought so bravely to tell. I plan to tell everyone. My generation must take ownership of these truths, we must be the changemakers.

A second thing that I found myself thinking about frequently, both while I was in Central America and now that I’m writing this reflection is this question: what is it about these people that allow them to go on? What allows them to look me, as a United States citizen, in the face? What is it that spurns humanity onward and is it as simple as hope? Or hope for the children, the next generation? Hope for the future? Is there a point where a human being is simply forced to leg go of hatred and grief and blame…to set down that burden? Or are these people just truly better, simpler, more aware than the people of my own country? We breed a lot of hatred in the U.S. over lesser matters than bloody massacres human rights infractions. The kinds of death people encounter in the states are hardly ever as inhumane, as grotesque as those that have occurred in El Salvador in the past thirty years. The deaths we encounter in the U.S. are antiseptic; censored; quick. Evening news. Nothing like the atrocities that Danner and Didion and Rosenberg and countless other journalists have described for the masses. The idea of dying peacefully of old age in a warm bed is certainly not an idea which plays in the minds of the Salvadoran citizen, perhaps not now and certainly not back then. What is it about Latin America that allows political violence to thrive?

Tina Rosenbergs answer is convincingly simple: “if I had to give just once answer, it would be: history. Most of Latin America was conquered and colonized through violence, setting up political and economic relationships based on power, not law. These relationships still exist today – indeed, in some countries they are stronger than ever”.

My eyes are really beginning to open, not only to the incredible and fortunate bits of my life that I am so thankful to have but also of what human beings can do to each other, and what we can do about it.

Fortunately, Salvadorans are doing something about it. While visiting we were lucky enough to be amidst a people engaged in the full throws of presidential elections, their election day occurring one week after we departed the country, on March 15th. I didn’t want to leave the country because, more than anything, I wanted to be standing there when and if the FMLN party was elected (my party of choice). I formed this opinion in large part after meeting with David Morales. As a group, we met with Morales, the key lawyer involved in the human rights investigation in El Mozote, and through vigorous translation, we gained a lot. I was floored at the amount of information he had in his arsenal.

When the war ended and the peace accords were signed, the Arena party took control and has held fast to that control until now. Under this leadership, the government of El Salvador completely aborted all human rights objectives. Amnesty was given to over one hundred military leaders that were directly involved in the mass killings, death squads and to those involved in the deaths of Archbishop Romero, the Jesuit priests and those living in El Mozote and other equally innocent neighboring hamlets. The government, under the Arena party, proclaimed nationally and internationally that the peace process is based on amnesty, yet David Morales made it clear that in the past decade, 22,000 people have been killed in El Salvador and of those, in 100 assassinations, barely 4 of them reach the court system. It would seem that in this country, violence is simply not investigated, and that when the police take on military functions, lives are lost in great numbers. As recently as 2001 and 2003 documented cases of torture are still being carried out. According to Morales, there is evidence to prove this. In fact, part of these “police” are termed the extermination squad with the purpose of “cleaning up the population of El Salvador” With the FMLN party, there is now, finally, after thirty years, real hope for truth and justice and for the righting of great wrongs. I have great, great hope within me for this country that I have come to truly love.

Now that I’m home, I feel intensely compelled to return. If I had the money in my bank account for the plane tickets, I’d fly tomorrow; no questions, no regrets. I feel deeply linked to the country, and to the people that live in those mountains and to my companions that I traveled with. I feel incredibly blessed to have had the opportunity, to have learned so much from Claudia, and from my classmates, teachers, friends, and from the culture itself. It is absolutely true that every single person has something to teach you and I cannot wait to teach others what I’ve learned. It is not only my duty, but also my promise to Rufina and to all the people of El Salvador, both the living and the remembered.

…………………………………………………………………….

April –May 2009, “Building Peace”

*Building Peace* is a mural project created at the Spencer Center for Civic and Global Engagement at Mary Baldwin College between April 25 and May 20, 2009. This mural was envisioned, designed and painted collaboratively by students enrolled in May Term and Claudia Bernardi.

Before students started the creation of the mural, they investigated and researched the fragility and successes of Peace Processes all over the world. They used their research and investigation as the “theme’ of the mural, proposing a new paradigm of community building through art.

*EXPANSIVE MURAL TAKES SHAPE OUTSIDE SPENCER CENTER*

*5/12/2009*

A dedication ceremony for the May Term mural was held at May 18 at the Spencer Center. Students talked about the design and read their artists’ statement, and a guests were treated to a slideshow of images from MBC film students during the Spring Break 2009 trip to El Salvador led by artist Claudia Bernardi, who also led the mural project.

MBC Artist-in-Residence Claudia Bernardi, right, talks with students creating a giant mural on campus A few weeks ago, it was just a plain, cream-colored, unassuming wall in front of the Spencer Center for Civic and Global Engagement. Today, the 70-foot span of brick dances with color and images that tell a story unique to Mary Baldwin College. Designed and painted by MBC students under the guidance of international human rights activist and artist Claudia Bernardi, the mural is the primary project of the three-week May Term course Building Peace in which 15 students are enrolled — some of whom recently returned from a Spring Break trip to El Salvador with Bernardi where they created a similar mural in collaboration with villagers.

Students work on the beginning stages of painting the mural outside the Spencer Center on campus When the mural is finished, an artists’ statement from students will explain the genesis of the mural and the meaning of elements they chose to include, such as a clinic founded in El Salvador by a friend of Mary Baldwin College and the women who hold up the familiar MBC cupola atop Hunt Dining Hall. The narrative will be housed in the Spencer Center.

members spent a morning in

April preparing

the brick wall

outside the Spencer Center for

a mural to be painted during a

May Term course led by MBC

Artist-in-Residence Claudia

Bernardi. The course, titled

“Building Peace,” continues

momentum Bernardi established

when she led students in

the creation of a community

mural in downtown Staunton in

2007. Watch the wall transform

with their effort during May

Term April 29–May 19

Visit “www.mbc.edu/spencercenter”:http://www.mbc.edu/spencercenter

for a slideshow of more pictures

Spencer Center for Civic and Global Engagement

*Women’s Work*

*By Bob Stuart*

*Published: May 14, 2009*

STAUNTON — A nearly finished mural on a 70-foot wall at Mary Baldwin College colorfully blends images of women in Staunton, the college and the world.

Students taking a class from artist in residence Claudia Bernardi have worked several hours a day on the mural for two weeks.

Former Ireland President Mary Robinson is depicted holding up the cupola of Mary Baldwin. Robinson, Ireland’s first female president, visited the college and spoke in 2005.

Images also show women from India, Australia, Mexico and other countries, and images of the Blue Ridge Mountains and local wildlife such as deer and bear.

The mural is painted in colors of bright red, blue and green.

Mary Baldwin senior Kirstin Holmberg said the project “brings together different ideas” and has been a stimulating collaboration.

Mary Baldwin student Hannah Scott of Richmond said she is “excited to do something that future students and the community can enjoy.”

Bernardi, who is teaching a three-week May term course called “Building Peace,’’ has quietly overseen the student work.

“It’s a story of women in the past, today and from other countries,’’ said Bernardi, who has worked in the fields of human rights and social justice, and has had her artwork displayed across the world.

Bernardi said she has worked to bring a balance to the project by at times asking students to reflect.

“Conceptually, I ask them to take a step back and look,’’ she said.

She said the students have collaborated on an intricate project.

“All the students are willing to come to a consensus on a project quite complex,’’ Bernardi said.

Scott said the mural also reflects the growing diversity on the Mary Baldwin campus.

Two percent of the college’s students are now international.

Mary Baldwin Spokeswoman Dawn Medley said students attending the college now come from Northern Ireland, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Zambia, Bulgaria, Germany, India, Jordan, Japan and Korea.

*The Story of the Mural*

The mural has a story of its own. It begins with a compass in the hand of a pregnant woman, pregnant perhaps literally but also symbolically with dreams, ideas, and possibility. The compass beckons us to follow on and leads us on a journey of hope. As we follow the path we find symbols of our obstacles and dreams. A black crow flies over, a symbol of the years of the Jim Crow laws that divided people as different class citizens. There is a blood drive representing the critical importance of health care and in another scene there is a teacher and children emphasizing education.

We see the compass again in the hands of a woman offering it to another woman on a bridge. Their clothes, faces, and ethnicity are different but the compass unites them, brings them together to nurture and develop the world. This unity is expressed with music, which is a symbol of how art can bring us together. From distant lands people come to play in the fields creating a common harmony that pulls our world together.

Our compass leaves us not to an exotic world but one we know quite well. The last scene is of three women holding up our cupola, Ida B. Wells, Mary Robinson, and Rufina Amaya, these women all have a connection to the college and represent our ability to achieve greatness. They welcome a student with the compass, accepting her into Mary Baldwin’s history. If we look back on our travels we will realize Mary Baldwin College has shepherded us throughout our quest toward a new world of unity and peace.

Mural Chicas, Building Peace, 2009

…………………………………………………………………….

YEAR LONG ART CLASSES IN PERQUIN: America Argentina Vaquerano (Dina), Claudia Verenice Flores Escolero, Rosa del Carmen Argueta and Rigoberto Rodríguez Martínez

I measure the success of the School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin as a community based and collaborative art project by stating that, today, the school is flourishing in the hands of our wonderful artists teachers, who continue to design, develop and carry on art projects in Perquin and beyond.

Emphatically, this is not a “Bernardi project”. This is a community project directed, guided, designed and facilitated by local people.

Weekly classes in painting, drawing, wood sculpture, paper sculpture, murals and many more inventive techniques are shared with children, youth, adults and the elderly.

I invite everyone to visit our web page: www.wallsofhope.org and Dina has included selected videos of the children’s classes on “YOU TUBE”:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VgMNndjGOZA

…………………………………………………………………….

August 2009- WALLS OF HOPE-COLOMBIA

While being in Huehuetenango in August of 2008, working with the group of indigenous women survivors of sexual violence, I received an email from Jorge Julio Mejía, Mejía, who was informing that he has seen a documentary about my work (“Artists of Resistance” directed by Penelope Price) in Switzerland. He saw that the work of art designed and facilitated at the *School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin* was “exactly” what the communities in Antioquia, Colombia, needed.

Would I come to Colombia to work in an art project?

On July 31, 2009, Claudia Verenice Flores Escolero, Rosa del Carmen Argueta and I, are going to Corcorná located in the highlands of Medellín, Colombia.

In Cocorná there is a group of victims of state terror organized under AVVIC, Asociación de Víctimas de la Violencia in Cocorná/ Association of Victims of Violence of Cocorná. More than 50 local people, families, youth and children and concerned citizens came together as survivors of state terror with the common goal of wanting to rebuild their communities.

Cocorná not only suffered the impact of violence and massacres but the influx of imposed poverty and obliged displacement causing the expected deterioration or extinction of communal identity, local economy and means of sustainability as part of their communal development.

The School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin will join the Association of Victims in their determination to keep the historic memory of the community alive by designing and painting a mural in a public location selected by the community where the participants of this project will narrate the stories of their past, their committed present and the dreams and hopes for the future.

…………………………………………………………………….

CHALLENGES of the School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin, El Salvador (and beyond)

The most recurrent challenge that the School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin faces is the securing of funding. The past 8 years coinciding with the Bush administration have been damaging for many reasons including the reduction or abolition of funding sources for international projects of this nature.

The School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin is a full-scale community art project in full operation in our communities in the North of Morazán and, as this report informs, it has started to travel through the American continent.

However, we still do not have a building of our own. We have been using different locations in the Cultural House, the Children’s library and most recently a class in the local elementary school.

Dave Sellers, Jim Adamson and Tyler Kobick are dear friends of our school. They are architects who have a long-standing connection with Morazan. They designed and built a health clinic in Rancho Quemado in 2006 and they designed and built the beloved health clinic at El Mozote in 2007. The communities of the North of Morazan are indebted to their generosity.

Dave, Jim and Tyler, have showed their interest and commitment to make the construction of the School of Art in Perquin a reality.

Needless to say, we do not have land and acquiring land will demand no less than *$50,000.* We remain optimistic, as our dear architects are, that funding will be, somehow, secured.

The list of people who we would like to thank is very long for our School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin only exists as a community effort.

It really does “take a village”!!

* We are dearly thankful to the *POTRERO NUEVO FUND* for their continued support to the School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin and the *New Langton Arts* that has served as fiscal sponsor to this project.

* We would like to thank *INTERSECTION FOR THE ARTS* for being our fiscal sponsor since our school was founded in 2005.

* We would like to thank the *SAN CARLOS FOUNDATION* that has supported our vision since our beginning steps into community development through art.

* We would like to thank *Jim Karstegl and The Women Self Education Fund,* from England for their support in paying the salary of Rosa del Carmen Argueta for a year

* We would like *Ellen and Joseph Borzelleca* for their generous donation to keep our school going and support payment of the salaries for America Argentina Vaquerano, Claudia Verenice Flores Escolero and Rigoberto Rodriguez Martinez.

* We would like to thank *Marlena Hobson and Paul Borzelleca* who donated funds, ideas, tools, books, etc, to the school and for their endless hospitality every time they open their home to me when I go to Staunton, Virginia.

* We would like to thank *Irani Escolano* for her generous donation.

* We would like to thank *Jeffrey Miller from Cadmus Editions,* San Francisco, for his donation and his commitment to donate the Publisher’s profits of “Pedro and the Captain” to Walls of Hope.

* We would like to thank *Mary Houghteling* a dear friend and supporter of this project who is currently helping us to develop strategies to make Walls of Hope a more secure and sustainable agency.

* We would like to thank *Justin Perkins and Tatiana Reinoza Perkins,* for their ongoing support by keeping our web page alive. It is thanks to them that you are able to read this report.

* We would like to thank *Catharine Curtin,* Kathy, who offered her generosity and skills in community building to disseminate the evidence of the work we do in El Salvador and beyond, among people in Canada and Mexico.

* We would like to thank *Fidelity Charitable Gift Fund from Judy M Huey & Leland D Levy.*

* We would like to thank the *Elizabeth Wakeman Henderson Charitable Foundation.*

* We would like to thank *all our friends* who, generously, have contributed to our School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin

* Virginia Anderson

* Rachel Bell

* Patricia English

* Margery Morel-Seytoux

* Jone Manoogian

* Gen Pilgrim Guracar

* Roger Ferragallo

* Katoko Sax

* Martha Castillo

* Cosette Dudley

* Mary Pat O’Connell

* Mark & Jana Tuschman

* Nina Koepcke

* Gertrude Reagan

* Lucero Arellano

IT IS ONLY JUNE 2009!!!

The year is not over yet! We still have half a year left to go around the continent creating community based and collaborative art projects.

We are committed to our work of art, education, human rights, community development, conflict resolution, diplomacy and social justice. We would have never been able to continue our work in El Salvador and beyond without the help and support of many people, confirming in this way, the interweaving of international effort that this community based project proposes.

On behalf of all of the community of Perquin

and The School of Art and Open Studio

Thank you!!!!!!!!!!

America Argentina Vaquerano (Dina)

Claudia Verenice Flores Escolero

Rosa del Carmen Argueta

Rigoberto Rodriguez Martinez

Claudia Bernardi

Download a PDF version of this report:

<txp:file_download_link id=”6″><txp:file_download_name /></txp:file_download_link>

Escuela de Arte Y Taller Abierto De Perquin (EARTAP)

Informe 2008 -2009

Paredes de la Esperanza, PERQUIN y más allá.

La creación de proyectos de arte continua expandiéndose y llegando a nuevas comunidades. Este es el caso del proyecto de muralismo comunitario creado por niños y jóvenes en Perquin, Arambala, Segundo Montes y Cacaopera en Morazán, El Salvador; en Toronto, Canadá; en Guatemala: Huehuetenango, Rabinal, Cobán, Ciudad de Guatemala y en el proyecto que estamos por comenzar en Cocorná, Medellín, Colombia.

Febrero 2008- Guatemala:

En Febrero, 2008, La Escuela de Arte y Taller Abierto de Perquin fue invitada por ECAP ( Equipo Comunitario de Asistencia Psicosocial) a trabajar con un grupo de promotores de salud mental, psicólogos asociados a ECAP y que trabajan con y sobrevivientes de masacres en toda Guatemala, como por ejemplo: Ixil, Ixcan, Chajul, Nebaj, Chimaltenango, Alta Verapaz y Baja Verapaz.

El mural de grandes proporciones (25 m de largo x 1,75 m. de alto) fue pintado en manta (tela) en las oficinas de ECAP en la Ciudad de Guatemala. Las 35 personas participantes de este proyecto usaron arte como una herramienta para indagar y preservar sus historias personales así como la memoria histórica de sus comunidades las cuales habían sufrido violaciones de derechos humanos y violencia implantada por terror de estado.

Nuestros compañeros y compañeras de ECAP identificaron al arte coma una nueva y monumental manera de relacionarse con las víctimas. Los trabajadores psicosociales, terapistas, activistas de derechos humanos trabajaron en colaboración con personas que eran sobrevivientes de masacres, creando colaborativamente “ El Tapiz de la Historia”.

Carmelita

Santos

Mural detail/ right section

Mural detail/ centre section

Mural Group/ Guatemala City, 2008

En Mayo de 2009, Adrianne Aron presentó su libro: una traducción de la obra de Mario Benedetti “Pedro y el Capitán”. En la introducción Adrianne habla de la triste recurrencia de la tortura como sistema, incorporada infamemente en las políticas de los Estados Unidos durante la administración de Bush.

La cubierta del libro tiene como imagen un detalle del mural “Tapiz de la Historia”, el cual muestra la catacumba de uno de los edificios públicos que se habían convertido en cámaras de tortura en Guatemala.

Jeffrey Miller, de Ediciones Cadmus en San Francisco, generosamente ha determinado que las ganancias del Publicista en el caso de este libro sean donadas a La Escuela de Arte y Taller Abierto de Perquin.

Muchas gracias!!!!!!! Jeffrey Miller y Ediciones Cadmus.

Agosto 2008/ Recuperando la memoria histórica con mujeres indígenas sobrevivientes de violencia sexual durante el conflicto armado en Guatemala

En Agosto de 2008, ECAP invitó a la Escuela de Arte y Taller Abierto de Perquin a trabajar con 30 mujeres indígenas sobrevivientes de violencia sexual durante el conflicto armado. Esta vez, Claudia Verenice Flores Escolero, Rosa del Carmen Argueta y Rigoberto Rodriguez Martinez me acompañaron a Huehuetenango en el Noroeste del país, en la frontera con México, mirando las montañas de los Cuchumatanes.