I was in the Bay Area teaching at the California College of the Arts in January 2020. The start of the year is always exciting; meeting new students is the best part of being an educator. In one of my classes designed to provide students with the theoretical background, training and basic information on how to create community-based and collaborative art projects, an International student from China came up with an unusual proposition. She would reach the manufacturers and CEOs of the 3M Company in Saint Paul, Minnesota, to request that the multinational conglomerate corporation that operates in the fields of industry, workers safety and health care, would agree to printing positive and proactive messages on the respirator and surgical N-95 masks. The N-95 mask had been distributed to all Chinese citizens and had become obligatory for everyone in China to wear since COVID-19 had emerged in late 2019 as an incurable virus that had caused thousands of deaths. Coronavirus, with its unleashed virulent force, was expanding rapidly all over China and beyond.

That was the first time that I heard anyone talking about COVID-19. Although I had read about coronavirus while I was visiting family in Argentina in December 2019, the description of the virus and its rapid contagiousness had not alarmed me sufficiently as to make COVID-19 the center of my concerns. With total candor, and a huge ignorance on my part, I asked the Chinese student if the N-95 mask was, indeed, efficient in protecting people against the virus. She responded that it was the only tool known to decrease the opportunity of getting infected.

People in China were frightened and desperate. She imagined that, since everyone had to wear a mask, to have positive messages printed on the mask itself would alleviate, even if in a small way, the catastrophic outcome of an unstoppable death. 3M never responded to her emails. The more we learned about COVID-19, the more relevant this project became. The semester progressed while COVID-19 stopped being identified as a “site specific” virus emerging from China. It was becoming a world pandemic.

It is interesting and debilitating to witness how easily one embraces denial. Despite the fact that by mid-February it was impossible to talk about anything without including COVID-19 in most of our conversations, and even when all forms of media and news where addressing constantly the expansion and harm caused by coronavirus, it took me a while to fully comprehend the seriousness and the deadly irreversible effects of the virus.

Then came fear.

And confusion.

And questions that had no answers.

And rapid changes that redefined what we were doing and why we were doing it. The week of March gth to 13″, 2020, divides a predictable past from a present and a future utterly unknown.

In person classes stopped abruptly in mid-March, being replaced by online teaching. Zoom, a platform that had been an alternative device for delivering information became, in 2020, how educators all over the world reached their students. Education pivoted in few weeks from a Socratic model of instruction based on meeting students in person providing the opportunity for debate and open forum, towards looking at the blank faces of perplexed students arranged on a

computer screen the size of a small postage stamp. Zoom fatigue was evident among students and professors, but there was hardly any opportunity to address this new malady with possible neurological damage ramifications because there was, apparently, no other alternative.

Language incorporated new wordings as synonyms of safety, “shelter in place”, “social distancing”,

“imposed isolation” were adapted by people with unprecedented docility, meeting

and congregating needed to be avoided at all cost. Dear friends and family were unreachable.

Social life was dismembered and re-arranged. An abstract version of love descended upon us like a massive dark monolete hard to interpret. Fear followed and persisted.

By the end of April, I returned to Virginia where I live. All courses continued online, final projects were presented, classes ended, faculty meetings followed, many new questions were shared among faculty who had tried and had managed to swim against a stream of adversities to complete curricula and were now exhausted and unsure of what would happen next.

May ended, June started.

I am not easily predisposed to feel depressed, but by mid-June a heavy sadness had nestled in my body, tactile if I touched my chest, or open my hands, or walk few miles with a heaviness that declared an irrevocable sense of loss.

I allowed tears to flow, sleepless nights to worry me, breathing to become arduous. This transit seemed necessary to, reluctantly, accept a present and a future that was redefined in accordance to a new pact towards survival. It was now blatantly obvious that all the collaborative and community-based projects that I had carefully designed and planned for 2020, as well as trips and visits to beloved friends and families in California, Argentina and Colombia, were cancelled or postponed. It was impossible to predict for how long and until when.

The numbers of new COVID-19 cases reported each day in the United States continue to increase logarithmically. The number of deaths are disproportionally higher among people of color; among the undocumented migrants who are terrified of being deported if they go to a hospital seeking for help; among poor people who have no way to stop working and safely shelter in whatever place they may have because they must continue working despite the dangers that they inevitably will encounter. COVID-19 has been mapping a new version of the territory of the United States. This is a map that shows an undeclared Apartheid, a system of institutionalized violence against people of color, segregation and social stratification in which not everyone has the same opportunities to face and survive coronavirus.

How, I wondered, could I design a community-based project during the pandemic?

What if?

I struggled to accept that life had been overwhelmingly altered due to COVID-19. What if ? I contacted the US criminal justice system to propose a community-based project via Zoom?

Could it be done?

Since 2015, Dina, Verence, Rosa del Carmen, the three Salvadoran artists and dear friends

and colleagues of Walls of Hope, and I, have been working within the US criminal justices system facilitating art projects with incarcerated youth. The outcome of these collaborations has been the creation of collaborative murals painted by unaccompanied, undocumented Central American minors, both male and female, detained in the United States. Each mural is a truthful visual rendering of the personal and communal histories of these boys and girls, ages 13 to 17,

who find themselves trapped in a system that they do not understand and from where they may, or may not, be freed any time soon. In June of this year, I was ready to encounter new obstacles that could impede me from facilitating an art project during the pandemic. Since April 2020, the Trump administration implemented aggressive immigration enforcement by deporting thousands of people to their countries of origin despite the fact that some of them might be sick with the virus or asymptomatic carriers of the coronavirus.

I contacted “MC”, a Lead Clinician with whom we had worked at one of the sites. “MC” had always welcomed the murals and had taken part in several of the paintings. This proposed project, relying on zoom, was going to be very different. We understood that we had to conjure a teamwork in which I was present on a computer screen while “MC” would be on site, distributing paints, brushes, and attending to the logistics of mural painting. “MC” summarized this partnership well, “You will be the voice and I will be your hands”.

I.

Silhouettes That Speak

Initially, I had to respond to many questions from the youth residential facility’s director and the US criminal justice system to which I could provide not a single answer. I had never worked in a community-based project via zoom, nor did I know if it was possible. I had to believe that it WAS possible. Despite the doubts, I was given permission to carry on this project. The starting date was scheduled for late June, extending to mid-July. The participants would be Central American, undocumented, unaccompanied migrant minors as well as incarcerated youth from the United Sates.

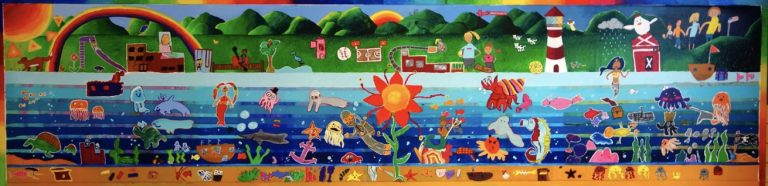

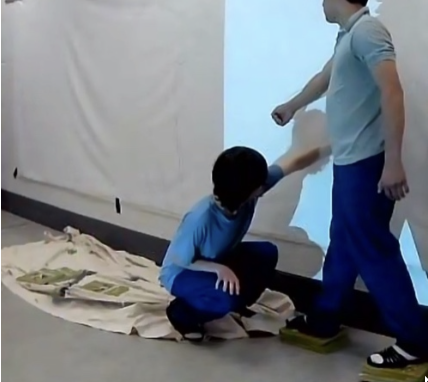

Silhouettes That Speak culminated after three weeks of intense artmaking as three murals, 6 feet tall by 10 feet long each, painted by eleven incarcerated youth, ages 13 to 17, relying on the Zoom communication platform to connect the young participating artists with the project facilitator. Using silhouettes as the basic composition of this project allowed the participants and the organizers to comply with the enforced 6 feet social distancing between each of the participating artists. They had the choice to paint a single silhouette or integrate them in a grouping. As the young artists traced the shadows of their bodies on primed canvas using an LSD projector to identify their contours, we talked about what it means outlining the mapping of the self that expanded from the way one looks like into how one feels, and why? They youth were encouraged to explore where sentiments are nestled within the body’s borders. Where are the memories rooted? Where are the hopes, and the fears? How could a symbol summarize the way the artist feels about the present and the future? Does it make a difference if the silhouette is standing, seated or kneeling? Armed stretched, or with no arms, or with arms up in a position of vulnerability? The choice of the position would determine the composition and the theme of the murals.

Central American minors, as well as US youth arrived in small groups of three to four artists each, identified by the names Alpha, Bravo and Echo. For three weeks, we met every day from

9:30 to 11:30 am and from 12:30 to 3:30 pm. The day before starting this project, I panicked.

How would zoom work to reach the young artists and to create a sense of community while we work? Would the participants relate to a woman who they did not know and who would speak to them from a computer screen?

How would their brain, and mine, respond to so many hours of screen time?

We had to believe that this was possible.

Alpha

A walking silhouette enters the mural from the extreme right, holding a black dog as a companion. The man and the dog are connected through a highway of intention, a journey that started a while back. It is difficult to guess when or where the path would end. Nature, flowers and winds, tears and love accompany the crossing. A red eye rests on the man’s left arm as a compass that will lead him, he hopes, to the route of less danger, the one the man cannot see but a pathway that he has to trust that he will find. There is only one thing the man knows for sure; he cannot return to Honduras. He has to continue going North. There are flowers in the dog’s body. This mythic dog is inhabited by nature and wisdom aiding the Honduran man to arrive to safety. He hasn’t been safe for a long, incalculably, stretched time, may be years, may be previous lives.

A potent central silhouette, populated by carefully chosen symbols, articulates several layers of intention in a beautiful, powerful and dignified way. The presence of environmental concerns crowns the head of a silhouette with hands up, vulnerable, as if being stopped at gun point. The neck is formed by colorful hands meeting in a LGTBQ demand of equality and gender rights.

The BLACK LIFE MATTERS fist calls for the urgent need to focus on a conversation about prejudice and racial confrontation during an unprecedented time in the United States following the infamous death of George Floyd, on May 25 ,2020. Following the killing, protests erupted in at least 140 cities all over the United States, with thousands of people taking to the streets protesting against police brutality.

The young artist who painted this silhouette is not African- American. He used his art to join a movement that is now unstoppable. His contribution to this mural connects his art to a relentless force towards social justice and a scream for change.

One morning, halfway in the mural process, the young artist who painted this silhouette did not join us. Was he unwell, I asked? He was well. In fact, he had been released. “E” had woken up early on the day that he was going to be set free. He asked permission to advance on his silhouette before leaving the prison. Only after he did that, he met his family who had been waiting for him for quite a long time in the parking lot.

The silhouette further to the left of the mural evolved from a tie-dye technique, using stains and marks in an agile composition. Seeing it completed, however, it is hard not to associate the dotted singularity of this image with the rendering of how COVID-19 expands and becomes contagious from city to city, place to place, person to person. Crossed legged and holding his hands up as if he was asking what exactly was going on, the young artist succeeded in alluding, poetically, to the pandemic.

A large brush connects the three silhouettes, with a single brushstroke commemorating the Rainbow flag, a multicolor design for the promotion of LGTBQ pride, dignity and equality.

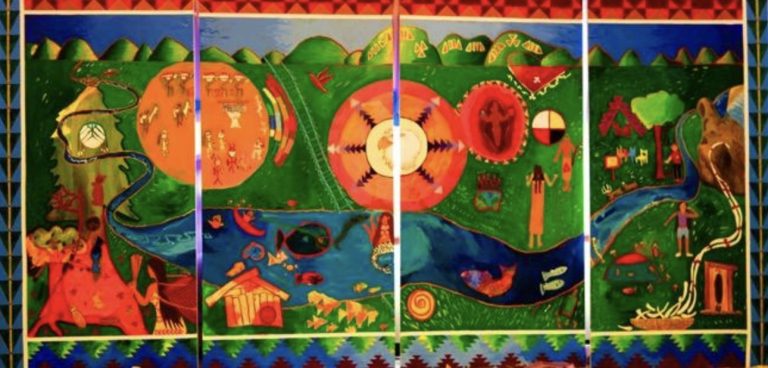

Bravo

In previous mural projects the guards and the case managers who accompany the young participating artists were present at all times, standing, usually not engaging in conversation, but following the development of the painting with genuine interest. During this mural project the guards and the case managers joined the young artists in the developing of the ideas, as well as in the actual painting.

Due to this infrequent collaboration the image towards the right of the Bravo mural is a female figure. This is the silhouette of a female guard who worked in partnership with “D”, a kind, circumspect, Mexican/ US young artist beholder of a remarkable talent to identify and paint details. A landscape of the Blue Ridge Mountains is depicted in the middle of the silhouette, embracing a tree of life that culminates in a Yin and Yang symbol describing opposite forces becoming complementary, interconnected. The chaos that governs most people’s lives may, if

reconsidered, become a force of positive power. There is a city landscape and a wall made of bricks, which represents an unclimbable border, a limit that will not be easily crossed. A sunflower and a maguey plant from Jalisco reminds the viewer that there is hope, even if one cannot see it, or imagine it possible. Hope will be always there.

“G” is a jovial, inquisitive, young artist who told me that painting the murals was the “most enjoyable thing that he had done in years”. Although he had never painted so large and with such a personal intention as this mural was demanding from him, he had no problem arriving to an image that represented what he was thinking and feeling at this time. “What is going on?

What will happen to me from now on? How will I get out of this place? How will I straight what I had so badly screwed up”. He had questions piling up in his mind as he continued painting.

Despite these many anxieties and doubts, he seemed always comfortable and well-disposed.

Being left-handed, his body had to do extra work finding a suitable position to relate to the mural such as, laying on his stomach to paint the silhouette from the bottom to the top. I found that astonishing! As he approached the zoom screen to ask me something about how to mix colors, I told him that his peculiar body location reminded me of José Clemente Orozco, one of the greatest Mexican muralists of the XX th century. In 1930, Orozco painted the murals at Hospicio Cabaña in Guadalajara. He did so with only one hand. He had lost his left hand and part of his left arm in an explosion accident when he was in his teens. Becoming a respected and beloved Mexican artist, he had to find inconceivable body positions to secure himself to the scaffolding and to maneuver brushes and paints while never loosing perspective of the image he was painting. “Man on Fire” is the central image of this magnificent mural depicting a blazing man in flames rising upwards, perhaps transiting from torment towards enlightenment, in the interior of the dome that occupies the entire cupula of the building that climbs 107 feet height. “G” had never heard about Orozco and could hardly imagine that anyone could paint a mural at such a height, propping himself on fragile scaffolding, using only one hand.

“G” was intrigued about the image and metaphor of the Man on Fire.

He reflected, “So…

. it is possible to change from torment to something else that is better, right?

“D” was resolved and determined to create a silhouette of himself kneeling and with an arm expended. The image, the power of its symbolism and the timely reason for that image to exist was unquestionably related to the BLACK LIVES MATTER movement and the peaceful demonstrations that brought together tens of thousands of people marching in big urban areas such as Los Angeles, San Francisco, Chicago, Philadelphia, New York, WA DC, etc, as well as in smaller cities across the United States, demanding justice for George Floyd and demanding the end of police brutality that had caused endless crimes and racial injustice. The United States was becoming galvanized after witnessing the assassination of an innocent, unarmed man, by a police officer, Derek Chauvin, who kneeled on this neck for 8 minutes and 46 seconds until he asphyxiated Floyd. To paint that silhouette within the US criminal justice system was subversive. It was risky and it was important. I did not inquire the artist’s intention, but it was obvious. Most significantly, the case managers, Lead Clinicians, the guards and the pass byers who saw this mural being painted did not object either. “D is not African-American. I found the opportunity to ask him why he had selected to paint that powerful image. He looked at me for a long moment and responded: “We all need to be Black these days”

One of the participating artists asked whether he could paint an image of himself that would not resemble a human body. He proposed to paint a tree, not only because he comes from a rural area where he learned to love nature and trees, but because trees are strong, and they know how to resist difficult times. He drew and later painted a tree that was inhabited by an iguana with whom the tree shared secrets of survival and longevity.

“R” painted himself in front of the television. He pointed out that being “brain dead” by watching a lot of TV was a great antidote to not dealing with pain. Does the pain go away? No, it does not. He may be watching cartoons, a favorite of his, or cheering during televised sport games, while his heart ached and bled to death. Was he feeling dead inside? Just a little. He felt damaged, and he did not know if his wounded heart could ever be mended.

The background of this mural is a bright yellow, chosen by the artists because it radiates hope and happiness.

The completed mural would be taken to their “pod”, the group of cells that the incarcerated youth share. The artists hoped that just looking at the bright yellow would bring them joy, even if it was for a short time, even if it would not be long lasting.

Echo

Echo was the last group to join the mural project. They had the opportunity to see what the

other young artists had done and learn about how the murals developed and what the meaning

of the images meant. They were better prepared to respond to question regarding composition,

how they wanted to paint their silhouettes, what body position to adopt.

“J”, from Mexico, crossed legged and reading, brought to the mural a cityscape surrounded by a

luminous sunset, facing the depth of a waterfront. Was this an image that he recalled? That he

had seen? He would not expand on the answer to that question. Mostly, he wanted to paint

something that he liked. Wasn’t that what art was for? To create realities not seen, or lived, or

that he may never encounter? He reads a book which brings him the opportunity to forget that

he is not free, that he is trapped within the US criminal justices system, that he does not know

what will happen to him next.

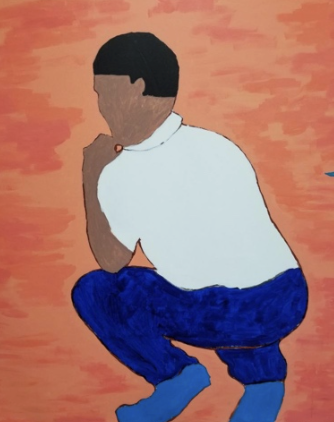

“J”, from El Salvador, did not want to face the viewer. He wanted to paint himself looking the

other way. He was born in a large city where, despite the massive size of it, he knew everyone.

Or so he thought, or he felt, while he was back home. Being in the US was awful because he

did not know anyone, and he did not want to know anyone either. And no one wanted to know

him. He felt invisible, not counted, not taken in consideration. He painted himself anonymous,

looking not to the front of the mural but beyond it. Plain clothes, unremarkable, just a white shirt

and jeans. He gazes, guarded, to a future that he does not understand, and he did not look for.

He knows that he has to be vigilant.

“I” thought about his contribution to the mural for days before he started painting it. He could not

stop thinking of it, even when he was in the shower, he said. His silhouette is formed by colorful

pieces of a jigsaw puzzle. Some of the pieces fit well. Some do not. That is the mystery of how

people take decisions some of which turn out to be dangerous. Can bad judgments turn into

good ones? Is there ever a way to go back to reconsider how the puzzle needs to be

reassembled? After the silhouette was completed, “I” wanted to add something else. A wing.

The wing of an angel. The painting of his silhouette may have given him the opportunity to

realize of something entirely good within himself, despite the bad decisions that he had taken

that brought him to be incarcerated. His silhouette, filled with doubts, but cradled by the angel’s

wing is one of the most hopeful images that I can think of.

“J”, the Mexican artist who painted himself reading, placed himself on the right side of the mural

holding the earth on one hand while the gradation of colors from deep blue to light yellows and

reds, address the urgent need to pay attention to global warming. The subtle, yet relentless,

change of colors show the damage already inflected on our planet while questioning what could

be done to restoring our pained world to green and a calm, cold ultramarine blue.

The background of this mural is painted with agile brushstrokes of a peach-colored orange that

travels, left to right and up to down with great energy. The young artists loved what they had

done. “I” was ready to paint a last contribution, a big banner with the word “Echo” taking

ownership of the piece. He had to be convinced that this was not necessary, that art has other

strategies beyond words to make the claim that a piece belongs to the artist.

My role in this mural conceived via zoom, developed into an interesting combination of art

making and cooking, “add a little of this, subtract a little of that other color you just selected. Do

not forget to clean the brushes in between making color mixtures”. The young artists would get

very close to the computer screen with paper plates acting as palettes, filled with mural paint,

asking how to mix “skin color”, or the appropriate tone for the background, or whether a red was

a better choice than a dark orange. I would suggest little changes until they would be pleased

with what they have come up with. Most of the times they were truly surprised that, for instance,

to get brown they would have to mix red with green, “Really?” “Yes, really, trust me!”

The completed murals would be displayed at the Alpha, Bravo and Echo PODs, where

individual cells are assigned to the incarcerated youth. On the last Friday of this project, “MC”

the Head Clinician who was my right and left hand in this project, designed diplomas with the

name of the artist, an image of the completed mural in which they took part of, and a

photograph of each of the artists while they were painting. “MC” was a fabulous collaborator in

this project, a wonderful team partner without whom these murals could not have been

completed. On a brief but meaningful last gathering where the youth had the chance to address

what part of the mural-process they liked the best, or provide any other opinion or suggestion,

“B” from Honduras, said:” I am going to tell you something that I have not said for a long time:

Thank you”.

That last comment is, possibly, the most meaningful reward that I could have hoped for as the

facilitator of this community-based project. Beyond whether the completed art piece is well

rendered or compositionally successful, the most important aspect of any collaboration is that

the artists appreciate their personal contribution and that of others. The artists had started by

sketching, drawing lines that appeared, initially, unconnected until the visual tracks crossed one

another, they converged, the silhouettes became a portrait, a person, a place, a landscape, an

intention.

Three weeks of art via zoom, gave me the certainty that, if we could create a project of this

magnitude within the US criminal justice system, there would have to be a way to replicate this

experience in another location, with other artists. I took few days to recover from “Zoom

syndrome”, a new health hazard that affects most people who spend long periods of time in

front of the computer screen and after a week, I started thinking where else a “virtual”

community-based mural project could be developed. During the month of August, I will have

preliminary zoom meetings with Sovereign Bodies Institute, an agency for generating new

knowledge and understanding of how Indigenous nations and communities are impacted by

gender and sexual violence, and how they may work towards healing and freedom from

recurrent violence. We will develop and organize a collaborative and community-based project,

most likely a mural, with MMIW, Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women. MMIW’s mission is

to bring the missing home and help the families of the murdered cope and support them through

the process of grief. The broader goal is to eradicate this problem so that the future generations

thrive.

These are challenging times. The numbers of people affected by COVID-19 continue to

increase day after day. There is a lot to be worried about, to be angry about, to feel lost or

anxious. I wish I could state that art may be a remedy for such loneliness, that art can fix the

many broken pieces of the life we used to have before mid-March 2020, that art can help

answer questions or mitigate the panic that creeps up out of nowhere.

Art cannot do any of that. But art is, if nothing else, a positive proposition that comes at a time in

which we are surrounded by darkness and doubt. Art is a minuscule contribution to envision that

something that does not exist yet, will exist because we are going to make it happen.

Together, in community, in partnership with other, because we believe we can.

Under the circumstances that surrounds us during the pandemic, to believe this is nothing short

of a miracle.