Collaborative and community-based project with relatives of victims of recent cases of police brutality in Argentina.

The Museum of Art and Memory of La Plata and the Provincial Commission of Memory, described the project that took place between 24 and 26 October 2014 in this way:

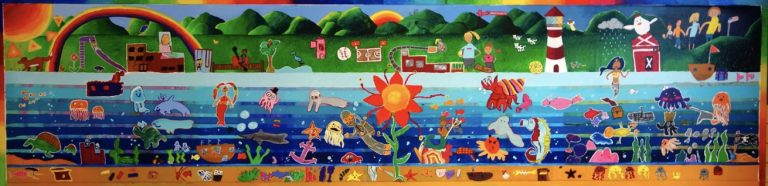

Relatives of victims of institutional violence made a collaborative mural on one of the walls of the Art Museum of the Commission for Memory of the province of Buenos Aires (CPM). The mural captured the memories, struggles and wishes of the families of Miguel Bru, Fabián Gorosito, Omar Cigarán, Sergio Jaramillo, Andrés Núñez, Sebastián Nicora, and so many other young people who have been subjected to torture, disappearance or murder by the Buenos Aires police.

I didn’t know the stories of these people. I had heard about the “easy trigger,” cops who could kill someone by beatings and impunity. But I had to confess that these issues came to me from afar.

Fernanda, facing a blank paper and a pencil in hand, asked me:

“How can I draw the truth? My son was found dead on the beach of Punta Indio, in Veronica where I live, and no one has ever told me what happened.”

Sebastian N. He was 16 when he was found dead. From that moment until now, Fernanda has searched, she has asked, she has knocked on a thousand doors. No one opens the doors to her and her questions. She decided to study law with the hopes of being able to use the laws in her favor. I suggested that she tried to ask her body the same question, how does the body respond when someone is expectant? She stood with parallel feet, head facing the front, hands open as if hoping they could receive something, mouth half-open from where she sighs had escaped and from where she absorbed fear.

And the truth?

You have to look for it.

Where is it? Will it be hidden in the earth?

Fernanda knelt, put her head sideways against the floor as if wanting to hear where Sebastian’s footprints could be, what where his last words, where his last steps would have taken him, from where he would come before reaching the river. He never got up from that sand, that earth and water that still keeps secrets.

Photo: Claudia Bernardi

This mural is narrated in the first person, uncovering the tragedies of desperate searches, of mothers, fathers and families who do not resign themselves to accepting that their sons were shot by “law enforcement personnel”. You can’t finish admitting that the cause of death of a child is “suicide” when he was found hanged in a cell. That same boy had told his father the day before that he was scared because the police were threatening him.

The stories were put together in pencil and on paper. A puzzle of pains

Photo: Claudia Bernardi

Ideas were transformed into drawings and woven into the surface of the mural. Each participant recognizing their place, also understanding the need to connect the themes in a coherent narrative chain.

“That’s life,” Maria said, lovingly painting a heart where the portrait of her son stared straight ahead. A “broken heart,” Mary clarified, “This is how we mothers and families are left with pieces of life.” This kind of pain puts the whole family in prison until it can be clarified what really happened and what were the hitherto unexplained circumstances of the death of a son.

Photo: Claudia Bernardi

Sandra G, is the mother of Omar C. Who was killed from the back while passing by on a motorcycle. Sandra wanted to be a “documentarian” and show the 9mm bullet that killed her son. When she and Omar had to be represented, she took a broader, more inclusive proposal, representing her son with a shirt and cap that could be any boy’s shirts and caps. The cap had a message: NOT ONE KID LESS

The younger brothers and sisters of the murdered boys participated on this mural by contributing ideas, suggestions, drawing and painting, talking about their family stories with terrifying clarity.

Photos: Claudia Bernardi

Elvira M. His son is in jail. She brought details and sorrow, the grievance that comes with going to visit him; the long bus journey; the queues of relatives with food, clothes, gifts for their imprisoned children. She asked:

“Can I paint a prison that is not so dark?”

Elvira painted the prison as it is now. Her son is inside a cell, naked and cold. To the left of that gloomy building, across the street where the bus that takes her to visit her son every Sunday passes, there is an open-door prison, literally without walls, in a green environment, where prisoners are given the possibility of working on farms, building furniture, learning some trade, feeling that life is not just to be wasted hour after hour.

On August 17, 1993, Miguel Bru, a journalism student, was tortured to death in the Police Station Number 9 of the city of La Plata.

Rosa Bru, his mother, said in a report:

“We had no contact with reality. Miguel’s father was a policeman, we believed in institutions. With Miguel’s disappearance we learned about police and judicial corruption, political complicity.” Rosa Bru also said that she discovered commitment and solidarity.

“Where are they?”, “Why did they kill them?” , “When will there be Justice?

Photo: Claudia Bernardi

Justice has been deaf, dumb, and blind.

Mirna N. represented the silences that she encountered during the long search for her son whom she never found, on the same road where Fernanda had her face crushed on the ground, trying to listen to the murmurs of her dead son, to find his footprints.

Gustavo J. He came on the first day but left soon. I never knew if he left upset. It seemed that something had bothered him. Everyone anticipated that he would not return. But the next day he arrived, with his wife and three children.

Gustavo and I had a small “cloud workshop” where I showed him some ways in which moving clouds could be represented. Gustavo was smart enough to ignore everything I had suggested by creating his own way of painting clouds and skies.

More important than the sky, the clouds, or the mural, was the brief conversation Gustavo and I had during the mural’s inauguration celebration on Sunday night.

“At first I didn’t understand anything that was going on. I thought it was an offence. I didn’t understand why you asked us to make those little drawings. And now, I see it differently. Now I understand what the mural means, what we were able to talk about in the mural. It is very strong. Thank you.”

Photo: Claudia Bernardi