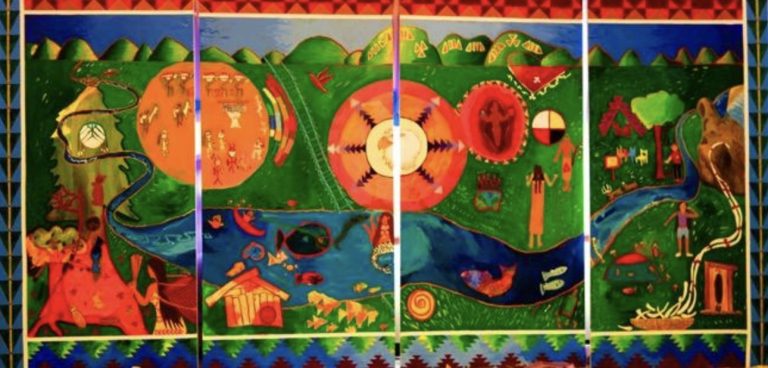

A collaborative and community-based mural painted by family members of disappeared citizens victims of the military dictatorship in Argentina

Relatives of disappeared people during the last civic-military dictatorship in Argentina, 1976-1983, who were able to recover the human remains of their family members through the work of the Argentina Forensic Anthropology Team, painted a mural in March 2014.

The Disappeared Are Appearing is a collaborative and community-based mural project designed, rendered and completed by the relatives of victims of state terror in Argentina. The participating family members of the disappeared had recovered the human remains of their beloved relatives through the tenacious and constant work of the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team/ Equipo Argentino de Antropología Forense, EAAF, a non-governmental, not-for-profit, scientific organization. EAAF was established in 1984 to investigate the cases of at least 9,000 disappeared people in Argentina under the military government that ruled from 1976-1983. EAAF applies forensic sciences – mainly forensic anthropology, archaeology and genetics- to the investigation of human rights violations in Argentina and worldwide. Utilizing forensic anthropology and related sciences and working in close collaboration with victims and their relatives, EAAF seeks to shed light on human rights violations and thus contribute to the search for truth, justice, reparation, and prevention of future violations.

In 2007, EAAF launched the Latin American Initiative For The Identification Of The Disappeared (ILID, Iniciativa Latinoamericana Para La Identificación de Personas Desaparecidas). This Genetics and Human Rights Initiative towards

the identification of the disappeared, focuses on using new DNA technology to dramatically increase the number of identifications of human remains of the thousands of people disappeared in Latin America for political reasons.

In the vast geography of the mural the relatives, turned artists, found a communal place to remember and to preserve their personal histories that narrated their long and desperate search for the missing family members, the painful lack or negligent responses received by governmental institutions and their persistent claim towards justice and accountability demanding trials that would condemn the perpetrators of human rights violation. Finally, they depicted a time of mourning after encountering the vestiges of their mothers and fathers, sons and daughters, sisters and brothers, husbands and wives, all of them buried nameless for decades until they were retrieved from oblivion by the EAAF.

Remembrance: Memories are interstitial segments of truth.

Memory, personal and collective, becomes militancy in the post-conflict period. Recollections configure our past and, consequently, our future vindicating people who we loved and who are looking at us from the other side of death, leaving us with a painful caress on our lips and with a question: Why are we still alive?

I am an artist. My artwork is born from memory and loss.

I design and facilitate collaborative and community-based art projects in regions of the world affected by armed conflicts, political violence and state terror. For victims facing the innumerable challenges of the postwar period, art can become a tool for community building proposing, and effectively establishing, new forms of diplomacy.

My artwork lives in the intersection of art and war.

A work of art is a “half open door” to something hidden, initially inaccessible, but tangible within a multitude of subterranean whispers never fully declared, barely audible, palpitating. Art proposes an investigation into the fragility of being while persistently searching for beauty. Beauty becomes a translator of brutality that choreographs pain by visually providing evidence of harm and violence.

My memories twist in an umbilical cord buried somewhere in Buenos Aires pulling me back forcefully. I have lived in the United States since 1979 where, as a socially- engaged artist and a practitioner of community arts, I develop, facilitate and help create collaborative and community-based art projects in the United States and internationally. For the last twenty-five years, I have worked with victims of political violence, state terror and forced exiles in El Salvador, Guatemala, Mexico, Canada, Colombia, Northern Ireland, Germany and Switzerland.

Until 2014, I had never worked in Argentina.

Remembering in adjacency to fellow Argentines felt too close and too raw.

My sister, Patricia Bernardi, is a founding member of the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team. As part of EAAF she has searched for, found in mass graves, and exhumed 796 Argentine disappeared; 632 of those remains have been identified through DNA; 45 without DNA and 119 without a body. The information contained in the human remains verified sex, determined cause of death and confirmed identities.

The disappeared are now appearing.

More than 700 human remains are still in custody at the EAAF headquarters in Buenos Aires.

Justice: A work in progress

On December 22, 2009, at the Federal Court house in Buenos Aires, the sister of a disappeared reflected: “The EAAF has found more than one thousand skeletons of the thirty thousand that there are missing. Where could the others be?”

After the military junta ended in 1983, Argentina regained democracy when Raúl Alfonsin was elected president. In this post-conflict period Argentina had to face the abuses committed by state terror against a large proportion of civilians. The violations of human rights perpetrated by the military dictatorship were carefully orchestrated as an effective method of repression based on torture, degradation and physical disappearance. This awareness exceeded the consideration of politics. It became a needed reflection on ethics and justice after a catastrophic, wounded history.

We do not forget. We do not forgive. We do not reconcile/ No olvidamos. No perdonamos. No nos reconciliamos.

These determined remarks that could be mistaken as intransigence have guided Argentina in the strenuous claim towards justice and accountability while demanding trial and punishment for the perpetrators of violations of human rights. Their actions were not “accidents of war”. The Argentine military junta crafted a well-organized system of persecution, abduction, and extermination.

Justice may take decades to convey its mandate.

The Trial of the Juntas started in 1985. This was a judicial procedure performed by a democratic government against members of a dictatorship that had ruled the country until months before the trial started. Argentina inaugurated a legal process never seen or accomplished before in Latin America.

833 witnesses gave testimony in 709 chosen cases.

Two generals were sentenced to life imprisonment. The other seven accused were convicted to many years in prison.

Justice may be fugitive.

In 1989, an imprudent new democratically elected president, Carlos Saúl Menem, granted amnesty to the convicted and condemned generals.

It took Argentina two decades to revoke this unlawful law. In 2005, the Supreme Court ruled that the laws that protected officers accused of crimes against humanity were unconstitutional.

Justice and art have in common that both disciplines assume that it can happen.

An artist is, above all, an optimist who trusts that something that does not exist yet, will become in the merging of craftsmanship, intention, experience, discipline and intuition.

The prosecutors and the judges of the trials against the military junta had to govern the field of law with purpose, skills, proficiency, restraint and insight.

With the lifting of the amnesties granted to the convicted generals Argentina re-commenced in 2006 the trials against the military junta. This new legal attempt not only condemned the men who violated human rights but, as urgently, the trials identified crimes that ought not to be repeated ever again.

Nunca Más.

These are crimes against humanity.

Since 2009, The Argentine Judicial Court has imputed 2,979 people for crimes against humanity; 856 of them have been trialed and condemned; 701 are still on trial; 524 are charged and accused; 499 have died before they could meet a sentence; 110 were absolved.

Justice can happen to face the moral implication of genocide.

A mural: creating an atmosphere of collaboration.

In 2014, I proposed to the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team the creation of a mural project that would be painted by relatives of the disappeared, family members who were able to retrieve the human remains of their loved ones after exhumations and DNA testing performed by the EAAF. This proposition was outside the guidelines and scientific protocol that the EAAF follows. This unprecedented collaborative art project, I argued, could be beneficial for the participants. After evaluating the reasons for which a mural of these unique characteristics could be created, EAAF was willing to support and facilitate contacting families of the disappeared soon to become artists.

EAAF develops a close connection with the families of the disappeared. The interaction with the relatives evolves over years; decades even, in the search for information of buried secrets. EAAF had never suggested an activity that included art. This mural would be conceived, designed and completed by a group of people willing to share memories endured through years of painful silence.

Recollections are traces, brief moments of lucidity or torment that design the imprecise cartography of our memories proposing a mapping of the self through time. Memories bring facts from the past catapulted into a flexible present that readapts and reconfigures within a precarious architecture.

Memories conform and confirm the presence of absent people among us. Their gestures and their voices approach with a gentle movement; the soft light that defined their faces the last time we saw them is clear now. These instances resemble tiny dots in a large drawing that needs to be completed with lines, dot-to-dot, line-to-line, until a final image is restored.

Captured.

Memories are a commemoration against forgetting.

Personal recollections expand into collective reminiscence, recovering a social archeology in which a majority is involved, elucidating realities filled with anecdotes, elastic and vital, liquid and fluid like rivers that merge into one another; they transit far away distances immersing in the frail permeable, mutant membrane of today.

Shared memories are a proposition of empathy.

Memories are artifacts. Facts of art.

Artists are creators of artifacts that evidence narrations infused by beauty and intention. Art, could be said, is an indefatigable attempt to conquer life. Creativity is a proposal of life over death.

Art may be the only apt language to address genocide.

Art is a communal tool for listening.

We are listening.

The disappeared were assassinated

The remains stopped being anonymous.

The families stopped waiting for their missing relatives to come back alive.

My sister Patricia works with casualties. She counts the dead.

I work with the ones who survived the massacres and are willing to record what happened to them within the field of a mural.

The bones can tell history.

The mural is a book of history without words.

Walls: Frontiers made of wind and earth, of past and present.

In any mural project, one of the initial challenges is to find a suitable location that would home it. Would it be an interior or an exterior mural? The walls that will receive the art are of utmost importance.

Where would this mural be painted?

I suggested that the mural could be painted at the EAAF’s headquarters office on a flexible surface such as canvas. After completion, the mural could be exhibited in an interior or exterior location chosen by the participating artists. It could even travel to be shown at different venues.

Luis Fondebrider, one of the founding members of the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team, suggested that the mural could be painted at ESMA.

I heard what Luis was saying. I absorbed the phrase that he had delivered, but it took me a while to fully grasp and assimilate the magnitude of the message.

At ESMA???

ESMA, Escuela Superior de Mecánica de la Armada/ The Navy Mechanics School, is one of 400 buildings disseminated all over the republic that functioned as clandestine centers of detention and extermination during the military dictatorship, 1976-1983, in Argentina.

How could a mural be painted there?

With the arrival of democracy in 1984, ESMA, the place of horror, had been reclaimed by the relatives of the disappeared, people who survived imprisonment, Human Rights Non-Governmental Agencies, poets, writers and artists. In 2008, ESMA now called EX ESMA, became a place of memory.

I had not known until Luis suggested EX-ESMA as the site for the creation of the mural that in the process of transforming this menacing complex into a place of remembrance, several of the main buildings had been ceded to human rights agencies such as the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, the Grandmothers of Plaza de Mayo and HIJOS, Hijos por la Identidad y la Justicia contra el Olvido y el Silencio /Sons and Daughters for Identity and Justice Against Oblivion and Silence. One of those buildings at EX ESMA had been handed over to EAAF.

The proposed collaborative and community-based mural was going to be painted upon two interior walls in the building known as ILID, Iniciativa Latinoamericana para la Identificación de Personas Desaparecidas/ Latin American Initiative for the Identification of the Disappeared. Blood samples of the relatives of the disappeared and genetic evidence of the human remains would be kept and guarded in this building to permit and prove identifications.

This place was a time capsule that would allow future restitutions.

It is estimated that more than 5,000 people were kidnapped and taken to ESMA where they were interrogated, tortured and eliminated. An imprecise count of over one thousand men and women were disposed of by throwing them alive from military planes, death flights, to the dark waters of the Rio de la Plata.

Among the relatives of someone abducted and beloved, a persistent, excruciating doubt settled in their consciousness like a tumor of sorrow that triggered an unanswerable question, “What happened to the disappeared?”

Are they alive and hidden somewhere?

Are they no longer alive?

Will we ever know?

The spacious lot of 17 hectares of land and thirty-four buildings housed a clandestine center of detention where the prisoners were interrogated and tortured. Ultimately, they were assassinated extra judicially. This was the result of a well-planned system to exterminate civilians who were never granted the right to a due legal process under state terror.

It is emotionally challenging to enter EX ESMA. Walking along Avenida del Libertador, a crowded and busy avenue in Buenos Aires, the visitor can hardly predict that once finding the door that ushers the path towards the interior courtyard, the first to be seen are large portraits of the disappeared, printed photographs attached to the front of buildings, declaring their being.

The images fastened to exterior walls of the buildings at EX ESMA show Argentine citizens smiling, shy or serious, with wide-open eyes ready to devour life. These are the portraits of the disappeared looking at us from their aborted youth.

Their presence is being felt in their absence.

They look at us.

We look at them and we wonder, not fully convinced but hoping nonetheless, if we could bring them back to us intact, preserved, as if their perilous journey and their senseless death could be annulled.

The walls at EX ESMA retain whispers and gagged screams.

Colors, the spectrum of light made memory

To paint a mural at EX ESMA could have been perceived as a provocation. Would the relatives of the disappeared accept coming to EX ESMA to paint a mural?

For the families whose relatives were kidnapped, tortured and who perished at ESMA the idea of gathering at the place where their loved ones were tormented proved an unthinkable proposition.

The invitation to paint the mural turned into a dynamic exchange of phone calls and emails.

My mother (88) and two nieces, my brother Martin’s daughters, who are Manu’s cousins, Manu himself, his wife and her aunt Maria Laura, want to join this project. I must tell you that they live in Mar del Plata, La Plata and Tandil but they are willing and ready to come to Buenos Aires because they are excited about this idea.

With a hug, Ana Sanllorenti

A group of forty-five relatives congregated at the EAAF’s headquarters office where I showed images of completed collaborative murals in El Salvador, Guatemala, Colombia and Ciudad Juarez, Mexico. The relatives of the disappeared saw history being told from the point of view of the survivors who painted their deepest fears as well as their relentless determination to procure a better, more just future.

How does a “memory” become a drawing and a scene in a mural?

Is it possible to reach a common, group memory?

How are the participants drawings selected?

Can all ideas be honored and used in a mural?

Are there ideas that are discarded?

Who takes that decision?

The artists-to-be were moved, inspired and frightened. They were concerned about their lack of creative proficiency. No one had done anything remotely similar to painting a forty-feet long by seven-feet high mural. At the end of the meeting they were willing to, at least, give it a try. These were sons and daughters, sisters and brothers, husbands and wives, grandchildren of a generation decimated by state terror. They had in common more than thirty-five years waiting to know what had happened to their beloved disappeared. Thanks to the efforts of the EAAF and the comparing of DNA, they had recovered the human remains of their relatives together with the evidence of their death.

This truth, they said, was hardly healing.

I read the proposed project and I think that this is a fantastic idea. My connection with the EAAF was too intense as to be so brief. You are part of my life and my affections. But the reason that originated this liaison is the same one that ended it. After recovering the human remains of my sister, it seemed that there was no need to remain in touch. It is a strange sensation, because one feels that there are still so many things to do, so many questions to ask. I love the idea of the mural; I love to be able to share ideas and thoughts with other relatives who had faced the same experiences that I did. I love that the EAAF can think of this new way to go forward after the restitution. I love to think of placing a brush stroke on the wall.

I shied away when I arrived at the third paragraph in the invitation and read the answer to the question “Where would the mural be painted?”. I have avoided going to EX ESMA. I did not have the strength. I thought of visiting it, as a way of masochism.

But this is the opportunity to face that block.

So, I would love to participate in this project.

Stella Azar

Thank you very much for this invitation!

I would like to tell you a little about us. We are two brothers; Rodrigo and I, each of us have families. My brother is married and has two sons, ages 9 and 7. I am also married and have five children, three girls and two boys between the ages of 4 and 11. We are sons of Carlos Miguel and “La Negra”, Lilia Mabel Venegas, both assassinated during the last military dictatorship. My father, Carlos, was kidnapped together with Rodolfo Achem in La Plata on October 8, 1974. That same day, the Triple A killed them. Their bodies were found somewhere in Sarandí.

My mother was kidnapped in Mar del Plata on May 4, 1978. From that moment on, she had been disappeared until May 2, 2011 when we got a phone call from the EAAF confirming that they had been able to identify the remains found in a cemetery in Mar del Plata. It was an enormous shock to receive this news after so many years that left us facing confronting sentiments. But after digesting it, we felt a deep calm, peace, and above all, the joy of having her back.

Once again, thank you for this invitation! I already talked to my brother and he is also very interested in participating in the mural, especially, for our children.

I am sending you a big hug! And thank you again!!! Manuel Miguel

The emails we received from the prospective participants told brief and moving personal stories. These were messages of unthinkable beauty and of sadness so deep that it appeared as if words had lost their compass and beauty had turned into sorrow and sorrow was becoming beautiful. Knowing that this paradox is the very kernel of art, each of these individual threads started embroidering a tapestry of life.

Theme, what is the story that this mural will tell?

This collaborative and community-based mural would occupy two interior adjacent walls, sharing a 90 degrees corner, in the entrance room of the building called ILID, Iniciativa Latinoamericana para la Identificación de Personas Desaparecidas, Latin American Initiative for the Identification of Disappeared People.

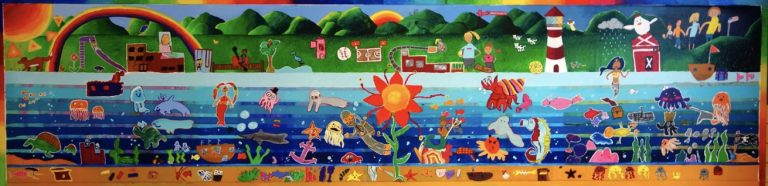

Fifty-two people, between 6 and 85 years of age, congregated in a pleasantly warm Friday afternoon of late Summer 2014 in Buenos Aires to create a mural that would tell the story of those who had died as victims of state terror in Argentina and those who, while still alive, remembered them.

We were entering EX ESMA, with brushes, with colors, with memory, with smiles, with histories and sorrow, with the future being held in children’s hands. Four generations were linked to the disappeared through the fragile, yet unbreakable, filament of truth attached to their beloved missing ones. There were mothers, siblings, husbands and wives, daughters and sons, nieces and nephews, grandchildren and even a great grandchild. The children referred to the disappeared as grandmother and grandfather.

“I would like my grandfather and grandmother to know that besides painting murals, I can also sing. I sing in a choir.”

Galatea Ciancio, age 11, Granddaughter of Patricia Dillon and Luis Ciancio, disappeared on July 12 Restitutions: Luis Ciancio, April 4, 2009. Patricia Dillon, June 26, 2012

The wheel of life was turning.

The first step of any mural project is to cover the surface with a thin layer of diluted mural paint applied with sponges, in large, uncompromising brush strokes that fill the totality of the wall with a luminous coloration.

The muralists drew, sketched and shared ideas that were discussed, discerning the theme that was emerging. It was important to start identifying background and foreground and prominent fields of color. One of the risks of working in collaboration with so many artists at once is that the mural could turn “cacophonic”, with too much information and not enough quiet background to produce a pleasant balance.

A sense of trust had to be developed among the artists muralists who were bringing their personal family memories as a delicate gift expanding from the intimacy of a recollection into collective remembrance.

Jigsaw puzzle pieces, some containing vignettes of personal histories and others empty, are metaphors of the obligatory “cut and paste” that the sons and daughters of the disappeared had to construct around the many stories that they were offered by people who knew their parents. They learned how to love them through intermediaries. Sons and daughters of disappeared parents carry with them the tragedy of an overwhelming absence. The effort of remembering is adjacent to the tenacity of collecting information.

How did they engage in a life of political militancy?

What were their parents doing at the time of their abduction?

What were they thinking?

Hoping not to think?

Understanding?

Not understanding?

Not being able to understand?

Relatives of the disappeared hold on to elusive discolored sepia Polaroid images, stained and fragile. These tenuous anchors imped their drowning in a sea of forgetfulness. Those incomplete vessels of presence show men and women frozen in an interrupted youth, an “absent generation” within a paradox of time.

Recovering the beloved bones solve one piece of the puzzle. These people had never been disappeared. They were kidnapped, they were in captivity, they were harmed intentionally, and they were executed without mercy. The human remains trace the cause of death.

Knowing the truth is alleviating.

The jigsaw puzzle travels the mural from left to right; some pieces contain subject matter; some others are silent, blank. The families of the disappeared would never learn all that happened in the segmented lives of their loved ones.

A vital tree frames the left side of the mural. Young men and women play guitars, they sing, they walk about, they meet friends, engage in politics, they debate, they march together for a cause. They seem to be living a normal and possible life, some days are calm and others, challenging. This is how life was before state terror.

The unleashed violence that aborted their plans and dreams made of Argentina a shipwreck. The country that existed before the military junta, also disappeared. After the military junta, the ones who left being victims of forced exiles and those who stayed, contemplated the remains of a shuttered nation.

From one wall to the other, the image that serves as a visual link between these two surfaces is the unmistakable round of the Mothers of Plaza de Mayo, the circular promenade of white scarves proclaiming a message of resistance and the demand for justice.

The participating artists concurred on a fundamental memory, a moment that would forever disattach the “past” form the “present”. It was a phone call. A member of the EAAF had contacted them by phone. Delicately, they were asked to join the EAAF in a meeting. The EAAF had something to tell them.

The artists remembered this instant as a striking lightening, “el rayazo”, a thunder so powerful, so potent that caused them insomnia, vomiting, imbalance. Some of them took days before they could respond to the call. They knew that the invitation would provide distressing facts. They arranged a day and a time to meet. They arrived early. They would learn that the human remains of their loved ones had been located and identified. In some instances, the cause of death was traceable and revealed. Associated objects such as garments, pieces of jewelry, even identification cards, were sometimes recovered with the bones.

Those were remnants of a life that existed, precious and unique.

A crimson colored DNA strand arranged as a long spiral, travels from one wall into the other. This double helix links and duplicates the mapping of identity.

“There will be a time in which none of us will be here. But our blood and the human remains, could still tell the story of what happened to us”

Federico Ciancio

A white spear of light surrounded by stars demarks the exact moment when the relatives had to abandon fantasies and hopes of a possible reunion with their loved ones to accept the unquestionable authority of death.

The disappeared were now appeared.

Their remains, collected and placed in an urn, were revered, identified and prompt for burial. This would be the last journey the bones would ever take.

A field of deep yellow meets a placid turquoise background. Within the warmth of golden light, a family congregates hugging a skeleton that seems, finally, to have arrived at safety. Someone embraces the bones, caresses the white presence as if this was an infant. The cranium, with vacant orbits filled with intention, trusting the care and love of the beholder, assumes a position of rest.

“After hugging our beloved bones, everyhting seems to revitalize”

Paula Bombara

A fingerprint encircles the permanence of identity. Justice can be demanded and, ultimately, obtained. The tree of life inhabited by endless flowers, birds, music and love stands above robust roots. The disappeared will be remembered forever through their absence.

We finished the mural on a Sunday evening. We hugged. We thanked one another. We cried. We were in disbelieve that in three days, more than fifty people, none of whom were artists, had been able and willing to deposit personal and communal memories within the topography of a shared mural.

We felt triumphant.

We had entered EX ESMA, the largest center of detention and extermination of our pained country, with colors, with trepidation and conviction, with sadness and hope.

We had conquered this space on behalf of the disappeared.

Photo, Viviana D’Amelia

- To Accompany the Mural

Written by the Artists

In this mural we wanted to tell what happened to us, what did we feel, what memories came back to us, what did we do, what did we dream of when we got the enormous news that the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team had found the human remains of our beloved disappeared.

We wanted to reveal the feelings that accompanied our labyrinthic search, our history resembling a jigsaw puzzle with missing parts; the commitment to our ideals, truth, democracy and justice. We looked at ourselves and to each other recognizing that in our DNA is where we could find the keys and the keyholes that led to the finding and the restitution of the human remains. Everything turned upside down, a thunder severed us, paralyzed us and revived us when we got the EAAF phone call.

In those days, time stopped being measured; the past and the future merged into a constant present filled with intense pain, but also with joy. Those moments are difficult to describe. These were new sensations, they resembled stars revolting against the sky becoming lights within ourselves.

Finally, we were able, we are able, to transit a grief that had seemed endless. The immense desire that we had felt to hug, to caress, to hold the hand of the person whom we had searched for during those many years of uncertainty, violence, unrest, was now resumed in an embrace from which we would never depart. A tender hug that changes us and transforms us. That thirst of searching that continues to be part of our identity acquires, from the time of the restitution, a new significance. The demand for justice accompanies us through a different path, where life feels more luminous, in which we look with new eyes to what is presented to us, knowing that all can be possible.

The recovery of those beloved bones determined a before and after for each of us, for our families. To have been able to transform those sentiments and memories in images in this mural, making of the individual a shared experience, is something that we are deeply thankful for. The magnitude, the reach of this embrace that the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team made possible, is incommensurable. We hope for hundreds, for thousands of new identifications, of new findings, of more encounters with the beloved bones of our disappeared.

We toast for that.

Stains of Life, a permanent shared memory.

Five years have passed since we painted the mural at EX ESMA.

I continue traveling to wounded areas of the world where I facilitate collaborative murals told from the perspective of injured communities. In teaching and in lectures, I have shared the outcome of the mural painted by the relatives of the disappeared in Argentina.

Yet, there are times in the middle of the day or at night, that I am sure I hear a voice that it is not mine. I may be asleep or more alert than ever before.

Did we really paint a mural at EX ESMA?

Yes.

That place of terror homes our mural.

We created a cartography that is not geographic.

Memory is a piece of ivory-colored silk stained by time, subtle, imperceptible at first, until the mark expands, and it becomes a continent.

This continent is our mural.

Claudia Bernardi

Berkeley, June 2019

The Disappeared who Appeared

Abducted Restituted

Guillermo Salvador Salinas 23-12-1975 14-08-2013

Eduardo Alberto Delfino 23-12-1975 03-10-2011

Daniel Jose Bombara 29-12-1975 17-06-2011

Norma Robert de Andreu 16-10-1976 28-03-2011

Marta Taboada 28-10-1976 23-12-2010

Juan Carlos Arroyo 28-10-1976 06-05-2009

Maria Eugenia Sanllorenti de Massolo 01-12-1976 18-08-2011

Patricia Dillon 07-12-1976 26-06-2012

Luis Ciancio 07-12-1976 30-04-2009

Camila Azar 20-12-1976 16-05-2011

Alicia Campiglia 08-06-1977 22-12-2005

Laura Feldman 08-02-1978 12-05-2009

Lilia Mabel Venegas de Miguel 04-05-1978 19-09-2011

The Artists Muralists

Gabriel Ciancio, brother of Luis Ciancio.

Maria Alejandra Falcón, wife of de Gabriel Ciancio, sister in law of Patricia Dillon y Luis Ciancio.

Matias Ciancio, son of Gabriel y Maria Alejandra.

Alejandro Marcelo Ciancio, brother of Luis Ciancio.

Clarisa Label, wife of Alejandro Ciancio, sister in law of Patricia Dillon y Luis Ciancio.

Federico Ciancio, son of Patricia Dillon y Luis Ciancio.

Silvina Sadoly, wife of Federico Ciancio, daughter in law of Patricia Dillon y Luis Ciancio.

Galatea Ciancio Sadoly, granddaughter of Patricia Dillon y Luis Ciancio.

Rocio Iturralde Sadoly, granddaughter of Patricia Dillon y Luis Ciancio.

Munu Actis Goretta, cousin of Norma Robert de Andreu

María Eva Arroyo, daughter of Juan Carlos Arroyo.

Sofía Arroyo, daughter of Juan Carlos Arroyo.

Marina Elsa Arroyo Linares, daughter of Juan Carlos Arroyo.

Gustavo López, brother of Roberto Raúl López.

Andrea López, sister of Roberto Raúl López.

Julieta Casiraghi, granddaughter of Roberto Raúl López.

Stella Maris Azar, sister of Camila Azar.

Camila Salimbeni, niece of Camila Azar.

Amalia Salimbeni, niece of Camila Azar.

Manuel Massolo, son of María Eugenia Sanllorenti de Massolo

Ivana Kiechowski, wife of Manuel Massolo, daughter in law of María Eugenia Sanllorenti de Massolo

María Laura Massolo, sister in law of María Eugenia Sanllorenti de Massolo.

María Eugenia Sanllorenti, niece of Maria Eugenia Sanllorenti de Massolo.

Ana Sanllorenti, sister of María Eugenia Sanllorenti de Massolo.

Reinaldo Martín Sanllorenti, brother of Maria Eugenia Sanllorenti de Massolo.

Andrea Gavio, sister in law of María Eugenia Sanllorenti de Massolo.

María Soledad Sanllorenti, niece of María Eugenia Sanllorenti de Massolo.

Marco Francisco Buschiazzo, nephew of María Eugenia Sanllorenti de Massolo.

Horacio Alfredo Salinas, son of Guillermo Salvador Salinas.

María Angélica Salinas, daughter of Guillermo Salvador Salinas.

Paula Bombara, daughter of Daniel Jose Bombara,

Andrea Fasni, wife of Daniel Jose Bombara

Pilar María Campiglia, daughter of Alicia Campiglia.

Alicia Elena Delfino, sister of Eduardo Alberto Delfino.

Marta Dillon, daughter of Marta Taboada,

Nana Dillon, granddaughter of Marta Taboada,

Jade Kupiec, great granddaughter of Marta Taboada

Albertina Carri, daughter in law of Marta Taboada.

Furio Carri Dillon, grandson of Marta Taboada

Manuel Ignacio Miguel and Juan Rodrigo Miguel, sons of Lilia Mabel Venegas,

Guadalupe Miguel, daughter of Manuel Ignacio Miguel and granddaughter of Lilia Mabel Venegas.

Ana Nora Feldman, sister of Laura Feldman.

Members of the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team:

Arquitect: Marcelo Castillo

Oureach: Cecilia Ayerdi

Photographs: Claudia Bernardi and Viviana D’Amelia

Facilitators and Logistic: Patricia Bernardi, Nuri Quinteiro, Carlos Rojas Surraco.

Artistic Director: Claudia Bernardi.