Collaborative and community-based mural project painted by undocumented, unaccompanied Central American minors currently detained in a maximum-security facility in the United States

By Claudia Bernardi

Marriage

Yesterday in my cell my pal asked me, Man, don’t you want to marry life

forever? And I answered, Why marry life if I can’t divorce death?

“Dreaming America, Voices of Undocumented Youth in Maximum-Security Detention”, Edited by Seth Michelson

- Vulnerability

The unpredictability of endless fear and the determination of hope

Entering a private maximum-security juvenile detention center in the US may confuse the visitor. The building is non-descriptive. The outside walls are light colored, and, at a distance, it may be assumed to be a school, even a private school. The architecture disguises the intention of the space and does not provoke fear.

The entrance gives way to a security checkpoint. Passed the inspection and the providing of personal information, a door opens to the interior of the jail. As one door opens, another door closes behind. For the unaccompanied, undocumented Central American migrant minors who cross this threshold these doors will become a frontier between freedom and incarceration, an unbridgeable gap between safety and threat, between dreams and despair.

This is a jail that homes undocumented minors from Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua. The inmates are between thirteen and seventeen years old. In fact, the day any of these minors will turn eighteen years old legally becoming an adult, they will be transferred to another maximum-security facility for prisoners over eighteen from which it will be ever less possible to find a route out.

In this juvenile center there are counselors. Because the incarcerated youth are minors they are expected to attend schooling. There are teachers and volunteers who attempt, in the best way they can, to assist the young boys and, although less frequent, sometimes girls, in providing them with enough attention and an educational structure that will allow the youth to feel that they are taken in consideration. That someone cares.

There are guards and there is trained personal that relates to the youth assuming that they are criminals. There are locked wards and there is a designated area that functions as Solitary Confinement. The youth walks from one location to the other of this space made of long corridors that feel like a maze with hands behind their backs, with vigilant sentinels ready to act fast and professionally in case there would be any misbehave from the undulant line of boys and girls who are being watched at all times by cameras.

There are no windows. There is no natural light. The air-conditioning maintains the space cold.

There is a rhythm of choreographed division of hours as tedious as they are efficient.

The rigid conditions that the young inmates confront at the juvenile center could be described as mild, if compared with the circumstances that each and all of them faced before getting here. They come from poverty and brutality. They have grown without supervision and in most cases, without a family that would protect them. Many of them have found in gangs and in organized crime a precarious sense of clan, of belonging, of being part of a group that may impede that they would be killed before they reach adulthood. Central American young males, both in their countries of origin and in the United States, fear that they will never celebrate their 18th birthday. This certainty is not the reflection of their pessimism as much as it is the result of the evidence that surrounds them, their friends and their communities.

Interestingly, they do not refer to this demolishing fact as part of their vulnerability. They have been trained to think and act, a day at a time, if they manage to survive one more day, they may have a chance after all. They still think that life may treat them “less bad” / “menos peor. They cannot conceptualize a “better” situation. Less bad may be as good as it gets outlining a more adequate expectation of a lifecycle that does not include improvement.

Each day that passes by and I get up; I speak, and I can hear, show me that I am not dead. And that is good.

Cada dia que pasa y que me levanto, hablo y escucho, me muestra que no me he muerto. Y eso es bueno.

“F”, 16 years old. Honduras

II. Unspoken Words/ Steps on Sand

A Visual Investigation of the Journey of Undocumented Unaccompanied Central American Minors Crossing the Mexico/ US Border

In 2013, The International Committee of the Red Cross, ICRC, asked me to create a pilot mural project using the visual arts as a liaison among youth affected by the effects of violence in the border city of Ciudad Juarez in the North of Mexico. This was a collaborative and community-based mural project developed and painted by twenty-six youth, ages 13 to 17 who were narrating in the field of the mural their fears, the history of their common past and their hope to achieve a future less violent, more benevolent that would allow them not to see crossing the US/ Mexico border as the only alternative to their survival. The International Committee of the Red Cross, the Mexican Red Cross and the Psychological Program Opening Humanitarian Spaces saw the role of art as pivotal in the process of conflict resolution in an area of the world where violence and Narcotraffic delineate every-day life.

As I was ending a lecture at Mary Baldwin University in Virginia, where I had just delivered the outcome of the mural project in Ciudad Juarez, a young woman approached me. Holding back tears and looking at me with an intensity that alarmed me, she told me that she knew where the young men and women were, those who had crossed the US border from Mexico. Many of them were in jail, she added. They had been incarcerated in a maximum-security facility in the United States.

I could hardly grasp what she was saying for the magnitude of information was beyond what I knew about this issue at the time. I had, in fact, heard about minors crossing the US/ Mexico border. I did not know how many minors had attempted the crossing. I had not learned that some of them would have ended up in jail.

I am an artist. I am a painter, printmaker and installation artist. My artwork is born from memory and loss. I am a Community Artist, which means that I am partaking in a new field of art that centers the creative process in facilitating community projects. My Community Art work has taken place for the last twenty-five years in parts of the world affected by war and violence. As a professor and educator, I design and teach classes that investigate the intersection of art and human rights, art and activism and the role of art as a cultural vehicle to demand and acquire social justice.

In 1992, as part of the investigation and exhumations of the massacre at El Mozote in El Salvador, performed by the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team, I drew the archeological maps that identified the finding in a mass grave of 143 human remains of which 136 belonged to children.

REPORT OF FORENSIC INVESTIGATION

EL MOZOTE, EL SALVADOR

December 15, 1992

Honorable Judge Federico Ernesto Portillo Campos

Second Court of the First Instance

San Francisco Gotera, El Salvador.

(…)

The physical evidence from the exhumation of the convent house at El Mozote confirms the allegation of mass murder. The evidence is as follows:

1. We have identified the presence of 143 skeletal remains, including 131 children under age 12, 5 teenagers and 7 adults. The average age of the children was approximately 6 years. There were six women, ages 21 to 40, one of whom was in the third trimester of pregnancy, and one man of approximately 50 years of age. There may, in fact, have been a greater number of deaths. This uncertainty regarding the number of skeletons is a reflection of the extensive perimortem skeletal injuries, postmortem skeletal damage and associated commingling. Many young infants may have been entirely cremated; other children may not have been counted because of extensive fragmentation of body parts. (…)

Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team.

The damage that I saw at the exhumation site at El Mozote, impregnated my life as if the residue of those tiny bones that resembled bones of a fragile bird and which we had handled with reverence knowing that they would disclose the truth of what had happened during the massacre was persistent enough as to produce a recurrent question:

How would it be like to return to El Mozote to work in art projects with children of the same age of those who we are exhuming today?

The thought was unsettling as it was constant.

Four kilometers North from the massacre place at El Mozote, I founded in 2005, the School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin/ Walls of Hope, a community- based project of art, human rights, education, diplomacy, and community development using the strategies of art making to rebuild torn apart regions affected by war. The “Perquin Model” has been successfully implanted in Guatemala, Colombia, Mexico, Argentina, Germany, Switzerland and Northern Ireland.

The Mexico/ United States border, la frontera, has become the most recent geographic epicenter where I facilitate the creation of collaborative and community-based murals painted by youth affected by the effects of violence. These murals could be regarded as oral history made visual; they trace whispers of unspoken words and follow steps on the vastness of yellowed desert sands.

Intrigued, I followed the recommendation to visit the maximum-security juvenile center where Central America migrant youth, both female and male, were incarcerated after being detained at the US border. Their crime, it seemed, was to have crossed the border without passport or the corresponding paperwork. There were more serious allegations identifying that some minors may have engaged in gang and cartel-related violence previous to having been detained by the US Border Patrol. This was, in fact, a severe accusation. Yet, the measures of punishment and castigation seemed disproportionate if the reasons for which the youth had crossed the border would be considered. According to the Office of Refugee Resettlement/ Division of Children Services (ORR/DCS), during the 2013-2014 Fiscal Year, 57,496 Unaccompanied Alien Children (UAC), mainly from Mexico and Central America, crossed the border illegally to the United States through Mexico. The unaccompanied undocumented minors had suffered all forms of abuse and violence linked to poverty, gangs and cartels in their homeland before embarking on a vulnerable journey which many times ended in extortions, brutal treatment and torture, rape and sexual exploitation causing an unprecedented number of victims of human trafficking.

United Nations officials have been trying to implement that the Central American children and families crossing the border would be treated as refugees fleeing armed conflict. Under the current US laws of immigration this proposal would lack legal weight. Yet, officials with the United Nations High Commissioner hope to increase pressure on the U.S. and Mexico to accept thousands of immigrants not currently eligible for asylum.

This disparity between how the legal system in the Unites States sees these minors versus how they could be seen if they would be treated with the respect and dignity that they deserve constitutes another border, a frontier shaped by prejudice and ignorance, a solid division that acquires the form of an endless wall thousands of kilometers long that, within the current Trump administration, proposes to be even higher, mightier, and more difficult to cross over.

The US criminal justice system sees the minors as criminals. As we embark in the creation of a community-based mural, the participants are considered artists. What we have in front of us is a white canvas, stretched and ready to paint upon. The expectation is open-ended focusing exclusively on what the participating youth may want to say, what they may want to express, what they could remember or address that which they rather forget.

The mural becomes a book of history without words narrating their journey, their identity, their fears and their possible future.

In spite of all, the mural will depict their hope.

- The Mural

Lights and shadows, lines and backgrounds; colors that narrate the life and death of children at the US/ Mexico border.

Since 2014, I have facilitated four mural projects created by undocumented, unaccompanied Central American minors incarcerated in maximum-security facilities in the United States.

Those four projects included the participation of the Salvadoran artists/ teachers from the School of Art and Open Studio of Perquin, El Salvador. Three of the murals were painted in collaboration with students and faculty from Mary Baldwin University as part of a course that I designed and have been teaching for over a decade called Permeable Borders.

To enter a maximum-security facility with twenty undergraduate female students expected to interact with young males in a maximum security juvenile detention center may be perceived as imprudent. “C.C”, Program Manager of the Office of Refugee Resettlement, Division of Children’s Service whose work focused on unaccompanied Central American minors in detention centers, welcomed this project while extending her help and assistance in any way we would need it. It was palpable that she was willing and, given the enormous restrictions and the rigidity of the criminal justice system, able to ease the life of the incarcerated youth. C.C. understood, early and clearly, the gain that a collaborative mural opportunity could bring to the participating artists.

The mural was going to be painted on a vast stretched canvas. Traditionally, murals are painted upon exterior or interior walls of buildings becoming signifiers of public spaces and urban landscapes. Given the fact that the participating artists could not leave the location where the mural was going to be painted, we made the mural movable, transportable after it would be completed and able to travel in order to disseminate the personal and communal history that it would recount.

My role as facilitator and project director is, exclusively, to ask questions. I do not paint the mural, I do not suggest images or colors, and I do not offer suggestions on how to resolve any given idea.

What is this mural going to be about?

What story/ stories would you want to tell in this mural?

Will the mural have a border?

Will the border be decorative, or will it have a theme?

Is there a past, present and future in this mural?

If, indeed, there were a time line, where would you place the past? To the right? Or to the left?

What about the future and the present? Where would you place them in the mural?

Etc.

We were working with an average of 50 participants. Within the maximum-security facility, the incarcerated youth is grouped in “PODs” of six to eight minors each. The participating artists could not congregate all at once in front of the mural. They would have to understand and comply to collaborating with many artists they would never see. The painting process involved the participation of each and all the POD’s, who would add and build ideas and fields of colors, one upon the others, while developing a subject matter that would be the theme of the final piece.

It is safe to say, that as educator, I was ready to face disagreements among the participating artists or controversy emerging from opposite ideas. I advised the MBU students to be respectful of the youth’s designs, to receive them and work with them developing visual resolutions to their proposed themes without interfering or changing the original ideas of the Central American youth. Conflict never occurred.

The different groups spent an average of one hour each in front of the mural. The vigilant gaze of the guards made us feel self-conscious as if the danger of being attacked was a palpable preoccupation. However, the young Central American artists were always polite, considerate, and easy to talk to and work with even when language would be an initial impediment to communicate freely since most of them did not speak English and only few MBU students could converse in Spanish. As it always happens, meaningful interaction follows when the communicating parts develop a sense of trust and respect for each other. Amongst fields of colors, drawings that started describing landscapes, loved and missed people, vignettes that described violence as well as luminous fields of calm areas, the participating Central American artists, the students and all of us, arrived to a comfortable and kind interaction filled, at times, with humor and celebration.

One of the participating faculty mentioned that she was a mother. She had a daughter. As a Honduran boy, age 16, was painting people being cut into pieces and being thrown into a barrel of acid, he said:

I grew up alone in Tegucigalpa. Since I am 10 years old I have not seen anyone of my family. I don’t even know if they are alive or dead. I grew up with a gang because they gave me bread and a place to sleep. Later, they made me do bad things. Tell me what nice things you do with your girl. How do you show love to your daughter? And your daughter, how does she know that you love her?

Yo crecí solo en Tegucigalpa. Desde que tengo 10 años no veo a nadie de mi familia. Ni sé si están muertos o vivos. Creci con las pandillas por que me dieron pan y donde dormir, Después me hicieron hacer cosas malas. Cuénteme que cosas bonitas hace con su niña. Como le muestra cariño a su hija? Y su niña como sabe que Ud la quiere?

A 15 years old Honduran boy, circumspect and rather shy, shared with us that he had been dreaming with the mural instead of having atrocious nightmares in which he re-lived killing people, or he was running away to avoid being killed. The minors are frequently medicated to allow them to sleep for they arrive to this facility in fear and profoundly traumatized.

Guards are unusually known for kind words. Yet, the guards we encountered at the maximum-security juvenile center underwent a transformation probably of a higher degree than the Central American youth themselves. It was clear for the use of their voice and their body language that they saw their “job description” as making sure that the “inmates” would not disrupt the order, would not misbehave in any way and would continue to follow and obey the inflexible rules that governed the facility.

Yet, one of them, whose task was to escort the participants from their cells to the improvised art studio, cautiously approached me. Noticeably moved, he said:

Art can save the life of one of these kids.

I am unable to say that Art could save anyone’s life but, I am absolutely convinced that what art can do is to erase the distance between THEM and US; between people from one side of any border and other people across the way. The creation of a community art project can expand the membrane that agglutinates people, isolating them from “others” caused by prejudice, misassumptions, ignorance or indifference.

This mural project was starting to become a new geography upon which a new reading of identities was being proposed. The guards no longer were punitive. The students were learning, the undocumented, unaccompanied Central American minors were artists giving testimony of their lives using brushes and colors.

What do we actually know about the undocumented minors?

About the reasons for them to travel thousands of miles from misery and depravation towards a punishing border that protects a country unwilling to offer safety to them as they could have imagined or hoped for?

Are we ready to consider that in 2016 almost 60,000 minors chose a perilous journey of disproportionate danger to get to the United States?

A large percentage of them ended up being incarcerated.

A 16 year old Nicaraguan girl, with a strong personality and a notable beauty who displayed an “aura” that permitted us to imagine that if she could get some help to come out of the difficult scenario where she was at, and could be ushered to a better realm of possibilities she would become, no doubt, a remarkable woman. She was a natural leader, a good collaborator, an interested listener, an astute thinker and an able diplomat.

“I want to thank you very much for this project of painting the mural because it makes me remember that I can still love. But I will return to my cell where I will have to forget about loving in order not to die.”

“Yo les agradezco mucho este proyecto de pintar el mural por que me ha hecho recordar que todavía se puede amar. Pero yo vuelvo a la carcel donde me tendré que olvidar del amor para no morirme.”

- A Bleeding, Flowering Heart

Images of Pain and Bliss, of Lament and Courage

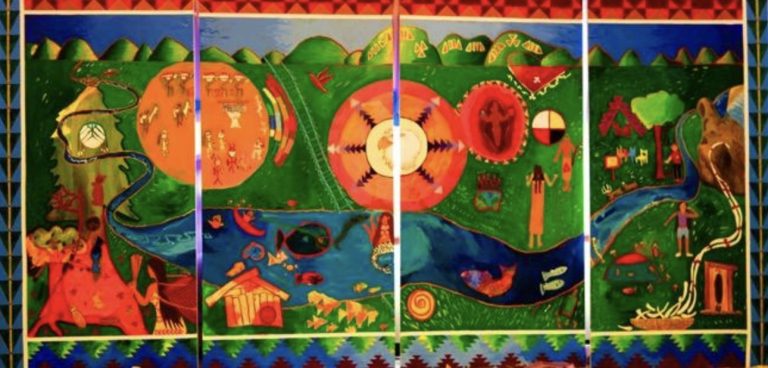

The most recent mural was painted in May 2017. It is 12 feet long by 6 feet high.

It has a border divided in equal rectangles that serve to inscribe an intention. Within the decorative segments of the border there are landscapes of visited villages and of places yet to be seen. There are rooms separated by bars; there are locks and keys that open jails to free people. There is a photographic-camera next to a pile of three books: one of Psychology, one of Business and the top book is an Art Encyclopedia. The artist who painted that vignette is a 15-year old girl who hopes, despite everything, to have the chance for education.

An angel can be seen at the extreme left, facing not the viewer but staring to the interior of the mural. We see the angel’s back with stationary wings and agile, elevated arms that are calling for someone, somewhere. To the right of the blue haired angel a tree divides today from yesterday. A birdcage jails a young man who is trapped in it. He seems sad and lost. He will be rescued by a small butterfly that brings messages of a possible day “less bad” than the one he inhabits at this moment.

A burning torn-apart heart delicately stands by a cemetery at night where the freshly carved graves have tombstones with Spanish names. These dead people known and loved have been abandoned behind. They had been hungry, thirsty, tired, injured, and lonely before they died. The trace of their journey ends in a distant map that expands over five countries, rendering Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua as a continent of sorrow.

A luminous summer night embraces tall skyscrapers. This is New York. A Salvadoran young man traveled from Chalatenango to New York, via Honduras, Guatemala and Ixtapec, Mexico, where he embarked on the deadly train La Bestia/ The Beast. He was robbed; he was almost thrown off that moving iron creature before he got to Nogales and succeed in crossing from Mexico to the US not knowing that he still had to traverse several states until reaching New York. After six months of journey he did arrive to Long Island. He had one name and one phone number written on a paper that was by then, almost translucent after being kept tightly in a pocket. The name was incorrect, and the phone number proved inexistent. He had no idea who else to reach in the United States.

He was now in the city of lights recognizing that not all that shines is gold. He slept in parks, in subway stations, discovering what it is like to be poor and hungry in the cold winter of the North. His feet were almost frozen, his hunger more pressing that any lack of food he remembered from El Salvador. His despair grew and his sadness was accentuated because he could not communicate with anyone. Or, no one was showing interest in communicating with him. A large frontal portrait appears underneath the New York buildings. His eyes are wide open and frighten asking us as well as himself: “What have I done? Why did I come here for?”

A woman in a hospital gown shows fragility. She will die of cancer. She is someone’s mother. His son, now in jail in the United States, wishes he could study to become an oncologist to prevent other women and their families from such grief.

Colorful buildings are assembled around a narrow street. This is a hamlet visited as a child that still appears in dreams as a safe place. To the right of the buildings, expanding towards the right edge of the mural countless butterflies of many sizes and colors are released, they disperse; they travel further than the Central American youth had ever traveled to reach this point.

A bleeding, flowering heart is the centerpiece of the mural.

This eloquent image offers despair in its anatomical rendering, and joy in the tender, colorful flowers that emerge from it.

The sixteen-year old Honduran artist who designed and painted the heart is from San Pedro Sula. He had not seen his family for a long time. He only knew where an older brother was. Although they were not close, he felt protected by him. After his brother was killed he knew he would be next in a list of young men to be executed. For what reason, he would never know. Besides, anyone could be killed for no reason in Honduras. He left Tegucigalpa in fear.

I asked him why he had painted a flowering heart.

I would like to ask life to allow me to flower at least one more time

Yo quisiera pedirle a la vida que me deje florecer una sola vez más.

Collaborative and community-based mural project painted by undocumented, unaccompanied Central American minors currently detained in a maximum-security facility in the United States

As the working day ended and I returned to the safety of my home, to the routine of preparing dinner and chose to retire early for the evening or to converse with friends or take a walk around the block, I could not abandon the thought of the youth in jail, submissive under the imposed unbending reality that was designing their life within the US criminal justice system.

How long would it take until they would be free?

This was as abrasive consideration that felt like holding an incandescent stone that burned and injured me.

The distance between the undocumented unaccompanied Central American incarcerated minors and the well-intended globally engaged selves seems to be astronomically apart.

Had it not been through the many fragile circumstances that brought us together to create such an extraordinary art piece, I would have never known of those young men and women who, at the very start of their lives had already seen, experienced, touched and learned defeating facts of violence and depravation that will sculpt their destiny from now on.

Borders, real or imposed, geographic, cultural or religious frontiers that fracture the social texture of communities all over the world, need urgent reconsideration to accommodate a reality of limits that must become permeable.

Endless interconnected threads of coincidences merge to rescue us from the punishment of solitude.

Claudia Bernardi

Staunton

October 2017